Cathrin Mayer interviews artist Flo Kasearu, whose socially sensitive practice has previously explored themes like domestic violence, small businesses, unemployment, gender, identity, freedom, patriotism, nationalism and the oppositions of public and private space. The following conversation took place prior to the opening of Kasearu’s large solo show BANANA – Build Absolutely Nothing Anywhere Near Anything.

CATHRIN: It's been a while since we last spoke. We collaborated on your first major solo exhibition in Estonia, Cut Out of Life, which was presented at Tallinn Art Hall in 2021. As I looked through my photos, I realised that my first visit to Tallinn was in 2018. It feels both recent and distant at the same time, considering how much the world has changed since then – before the pandemic, before Russia’s war on Ukraine. That war has profoundly impacted Europe, particularly the Baltic states, given their history as former Soviet republics.

Your exhibition at Tallinn Art Hall focused on domestic violence in Estonia. Now, as you install another major solo show at Kai Art Center, I’m curious – what is the central theme of this exhibition?

Your exhibition at Tallinn Art Hall focused on domestic violence in Estonia. Now, as you install another major solo show at Kai Art Center, I’m curious – what is the central theme of this exhibition?

FLO: This new exhibition explores the dynamics of public and private space through the lens of the NIMBY (Not In My Backyard) phenomenon. BANANA invites visitors to engage in discussions about urban and rural development, public participation, local values, and property rights. It examines how inclusion and exclusion shape contemporary development and the complexities of land use. I am currently installing, and the majority of the works are produced on the occasion of the show.

The title, BANANA, doesn’t seem to have an immediate connection to those themes. Your work often plays with language in a subversive way. Does this exhibition continue in that direction?

Yes, absolutely. About a year ago, I came across the terms NIMBY (Not In My Backyard) and YIMBY (Yes In My Backyard). These labels describe opposing attitudes toward development – some people resist large projects in their communities, while others actively support them.

Right now, Estonian society is deeply engaged in this debate, but instead of choosing a side, I was drawn to BANANA, which stands for Build Absolutely Nothing Anywhere Near Anything. This exaggeration reflects the paradox in modern development: we need progress, but we also resist its consequences. I am exploring these paradoxes through the concept of energy security – an especially complex issue in Estonia due to its history and development.

Can you tell us more about these special circumstances?

After regaining independence in 1991, Estonia had to transition from being fully integrated into the Soviet energy system to an independent, market-based system. The country worked to reduce its reliance on Russian energy imports by integrating with the European energy market, investing in domestic resources like oil shale and renewables, and developing connections with Finland and Latvia.

EU membership in 2004 accelerated this transition, and the goal has been to synchronise Estonia’s electricity grid with the European system, cutting ties with Russia’s BRELL network. However, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine drastically altered the energy security landscape across Europe. Now, Estonia is pushing to achieve full energy independence as quickly as possible.

How did you get interested in this topic in the first place?

I had an internship at a local sustainable energy company in May and June 2024. As part of my internship, I started attending meetings in many villages where a wind park would be built. I was also aware of this process, since wind turbines would be built near my country house. In the initial meetings during my residency, I mostly encountered optimistic, pro-wind individuals – mainly YIMBYs. Most of them were landowners who stood to gain the most financially if a wind turbine was built on their property.

However, as my time at the company progressed, I started noticing more opposition and a growing number of arguments highlighting the downsides of wind energy development. By winter, the opposition had escalated dramatically, much louder and more present in the media than I had expected. But, of course, energy is something everyone is connected to, and, in a way, dependent on. So, in a way you could say that since the internship I have been preoccupied with exploring the political implications of the backyard.

Can you tell us more about them?

The backyard is always smaller than the number of projects – or the ambitions of those pushing such developments. Wind farms, nuclear power plants, solar farms, high-voltage lines, Rail Baltic, military training areas, real estate developments – not in my backyard, please. Yet, these projects must go somewhere.

As space becomes increasingly developed, the backyard has transformed into a sacred and politicised battleground. Every metre of land is being claimed, bringing large-scale developments closer to people’s homes. This proximity stirs a mix of emotions – resistance, frustration, and, in some cases, acceptance – shaping the ever-growing tension between progress and personal space.

Estonia is widely recognised as one of the most technologically advanced and startup-friendly countries in the world. It’s a leader in AI, cybersecurity, and digital governance. I imagine there’s significant pressure to continue developing infrastructure to maintain Estonia’s competitive edge in the global market.

Yes, innovation and technological advancement are critical, but there’s also a paradox at play. Highly developed societies should be focusing on consuming less, rather than accelerating consumption. The challenge is finding a balance between progress and sustainability.

That’s true, though global trends in recent years seem to be moving in the opposite direction. Estonia, however, has rapidly modernised since gaining independence, with a strong focus on digital transformation, governance, and entrepreneurship. Given this pace, it might be able to implement new energy systems faster than other countries. What concrete plans are in place for this transition?

Estonia’s landscape is well-suited for renewable energy solutions. About 50% of the country is covered in forests, and 30% is agricultural land, with a relatively low population density. The government plans to construct large-scale wind farms, both on land and in the Baltic Sea, to generate green energy from wind, solar, and biomass.

Estonia aims to achieve 100% green and sustainable energy by 2030, well ahead of the European Union's 2050 target.

One major project which will be decided upon next year is how much money should be invested in offshore wind farms in the Baltic Sea. The challenge is deciding where these wind farms should be located. While urban areas demand energy, rural communities bear the impact. Naturally, landowners in the countryside are more affected, which has sparked intense debate.

What are the main concerns surrounding these developments?

There are multiple layers to the issue. First, there’s the visual transformation of the landscape – wind turbines are massive structures, and their presence alters the horizon. Beyond that, the movement of their blades creates shifting shadows throughout the day, which can be disruptive.

Then there’s the noise factor. Advertisements claim that wind turbines generate as much noise as a modern refrigerator – asserting they are pretty quiet. But the reality is different. People living near wind farms report a constant low-frequency hum, which can be unsettling over time.

Financial compensation is another point of contention. The government has proposed small amounts per year for residents living close to a wind turbine, but many feel this is inadequate. Property values are also at stake – land near wind farms tends to decrease in value, while land further away may increase.

The transition to green energy is crucial, and it's great that Estonia is both efficient and eager to be at the forefront. However, this is a complex process that the government aims to implement rapidly. While the population likely supports the shift, they also face significant changes in their daily lives and surroundings.

Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Estonia has drastically shifted its energy policies. How has this war affected the Estonian people?

The war has had a profound impact. Estonia has taken significant security measures, such as increasing defence spending. It’s also home to NATO’s Cyber Defense Centre, playing a key role in countering Russian cyber threats.

In terms of energy security, the situation has heightened concerns. Unlike a single power plant, which can be a major target, wind farms are distributed across the country, making them less vulnerable to an all-out attack. However, this widespread placement means more communities are affected, leading to growing fears that their land – whether the actual site of the wind farm or nearby – could become a potential target.

We've spent a lot of time discussing the reasons behind your exhibition, which is crucial for understanding its context. However, I’d love to dive deeper into the actual concept of the show. What artistic strategies and works have you developed to explore these highly political and complex societal issues? Could you describe some of the key pieces in the exhibition?

One of the key elements in the show is the installation Nimby (2025) using a fence from the house that used to be next to mine. Sometime ago a real estate company purchased the property and built a huge building next to mine. Today I feel like my house has a “big sibling” which it has to exist next to. This development is a good example of the structural change in Tallinn. I was able to collect the fence of the older building that, like mine, also was built in the beginning of the 20th century. I carved it and reinstalled it at Kai.

When you enter the show you look down on it from a higher platform but you cannot enter it.

Inside the fence I have placed a series of paintings of various sizes of larger scale that I combined as objects: two paintings are juxtaposed similar to an advertising display and placed on the floor. The series shows silhouettes of people that are engaging with an anonymous dark element. Multiple figures are hugging this element, or lying next to it or sitting around it. This anonymous element could be interpreted as the last tree on a piece of land that has to be taken down or it could be the foot of the wind turbine which they welcome as a new family member. The paintings are placed on top of a beige colour similar to the tone of sand. At first, I wanted to use a green carpet, but then it almost became too close to reality. The beige carpet adds another level of abstraction and it implies the idea of a desert, a deserted unnatural landscape. This estrangement also reoccurs in the figures that have schematised eyes that look like socket inserts. So even the human figures are so to speak “electrified”.

It is super interesting how you, like with the internship, “use” real-life events to narrate a story; it makes this complex topic much more approachable… since you mentioned your house, I would like to talk about it as well later, since it’s not only the place where you live, but you have also made it into a museum… but before we do that I would love to hear more about the works in BANANA.

So another important work that is placed next to Nimby is Statue of a Woollen Sock.

It is an amorphous object 260 x 325 x 180 cm as a sock that is so to say peaking over the fence of the title. Like the Statue of Liberty, I made it out of copper. For this work I was inspired by a study called “New Energy Landscapes” published by the Swedish Institute last year that examines energy production in the Baltics. One of the outcomes was that, especially in Lithuania, people could just simply wear woollen socks in winter to cope more efficiently with the cold. Often people want to run a round in T-shirts at home during the winter, but that is not necessary, it is also okay to not have summer temperatures at home during the winter months. It’s also something that everyone can do because putting socks on doesn’t need any complicated infrastructure. So, it speaks about this, but the way this work is in dialogue with the title is also symbolically interesting, as the giant sock is peeking into the back yard. With the American reference that is present through the title of the work it does say something about the relationship of the US and Europe, which since the second presidency of Trump has drastically changed, and the US is trying to dominate Europe on so many crucial levels. At the same time, since Estonia is so close to Russia, the giant copper structure could also represent it as this constant threat. I also thought about the militarisation of Estonia that had to happen since the Russian invasions. The military needs training areas and people are afraid that these will be close to their houses. So, the sock has these multiple implications and levels of meaning that of course can also be interpreted differently by the audience.

I think that the dialogue between the two works is interesting and it’s such a good example of the way you work... the conceptual combination of ready-mades taken from life, but then also all of a sudden we are confronted with paintings that are also objects and the ambiguity of the scenes that we encounter there as well as in the sock statue in which you take something so harmless and generic like a sock and turn it into a symbol that stands for all the potential threats that we are currently living with. The rather undefined shape also transports this feeling that we often don’t know exactly what it is that could be a threat or that makes us anxious, it's just this unspecified mixed situation. In this ambiguity lies a subversive power that is able to make the audience aware of these often-blurred circumstances. With the reference to the Statue of Liberty you are also making a connection to this public icon that is almost like a piece of pop art. The way you play with symbols and the public space is also present in another piece titled Fridays for Future. Can you tell us more about that?

Yes, so for this piece I used five big refrigerators to form a gigantic cross, the top of which can be seen from everywhere in the show.

The idea for this work came when I heard about the claim that the wind turbines should only be as loud as a fridge. All of the fridges are supplied with electricity and therefore also make sound. The cross is not only just a universal symbol, but I want to reference the Victory Monument to the war of independence, which incorporates a large-scale cross, located on Freedom Square, which was erected as a memorial to Estonians who have fought for freedom and independence.

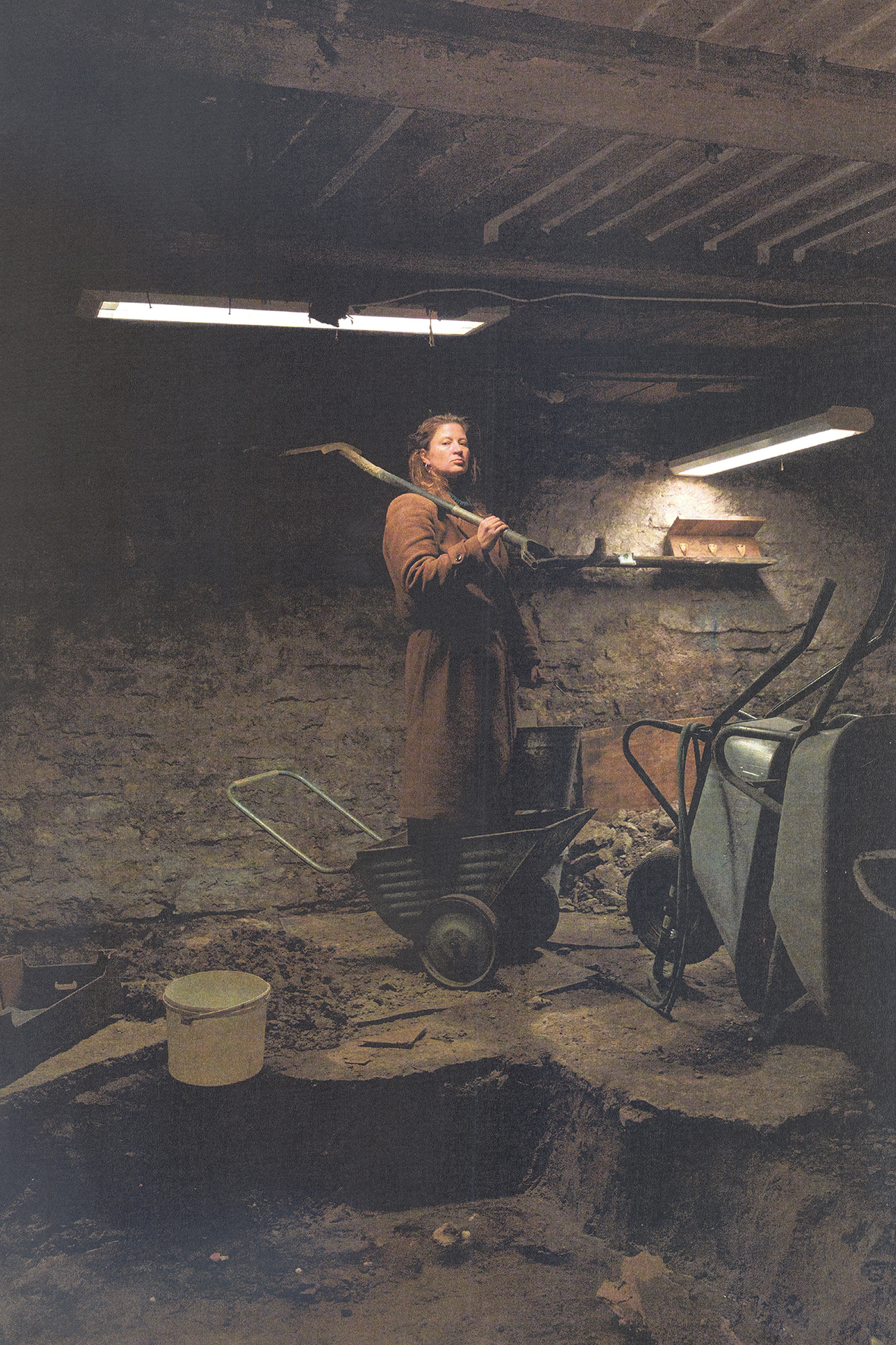

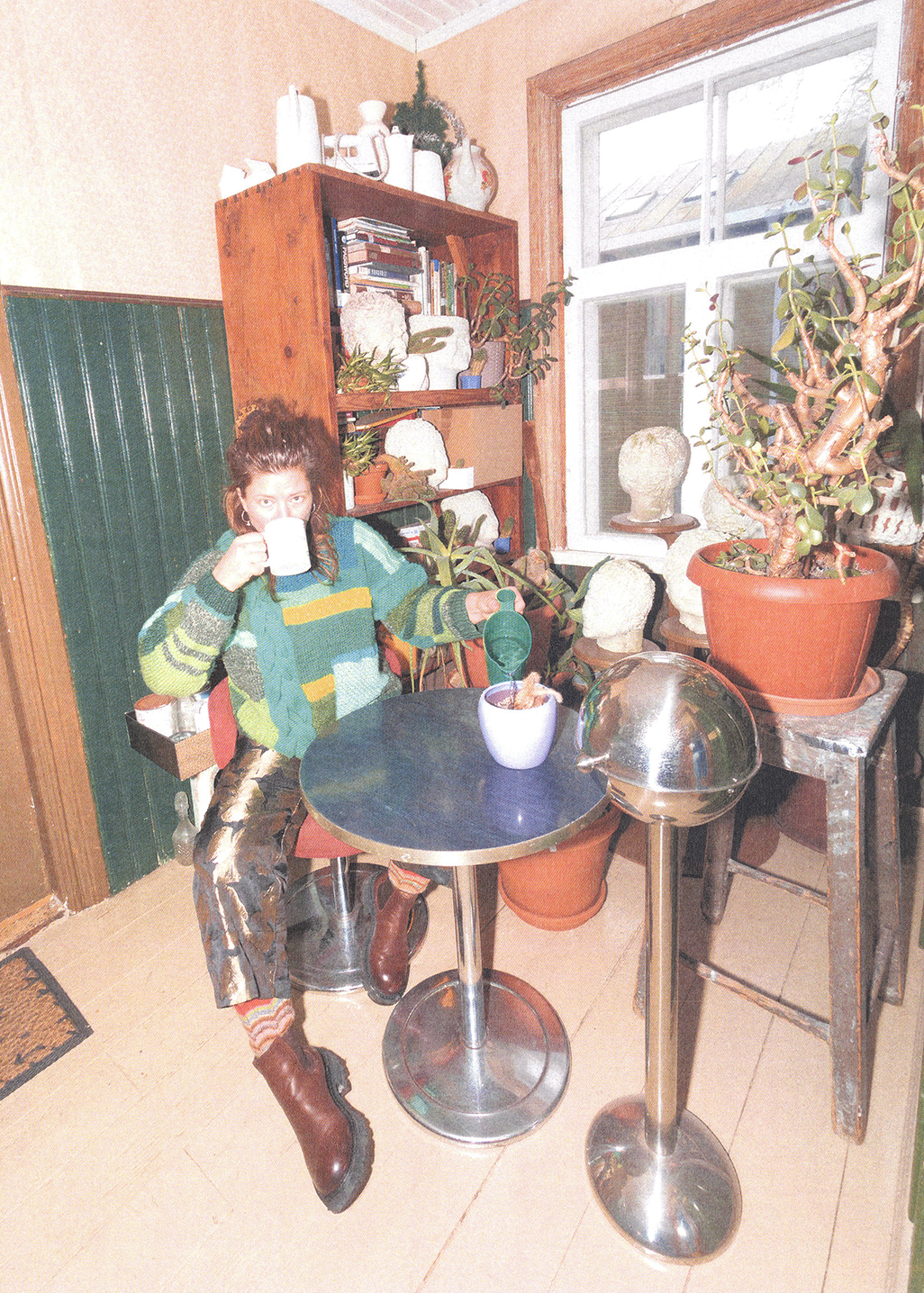

So this sculpture is also in dialogue with Statue of a Woollen Sock (2025) referencing large public monuments that carry a lot of collective history and value… I would like to talk a bit more about this importance of the public in relationship to the private through your house museum. The house that you currently live in, which we have already mentioned, and which was built in 1911 by your great-great-grandparents, reflects Estonia’s complex history. Originally a family home and spice shop, it was nationalised under Soviet rule after World War II, forcing your ancestors to flee in fear of deportation. Following Estonia’s independence in 1991, your family began the long process of reclaiming the property, a responsibility passed down through generations. Once you regained access to the house, you found it had been vandalised – people had used it as a temporary shelter, and it had been a target for thieves. After a renovation process, the museum opened to the public in 2013. It features art pieces, a collection of artefacts, and an archive spread across the house’s eight apartments, attic, and basement. The backyard includes a garden with open-air installations and a children’s play area, while the museum also houses a functional library and a gift shop.

Do you remember the exact moment when the idea of turning your house into a museum first came to you? What was the museum landscape like in Tallinn and Estonia at that time?

Do you remember the exact moment when the idea of turning your house into a museum first came to you? What was the museum landscape like in Tallinn and Estonia at that time?

The idea for my house museum didn’t come from a single “big bang” moment. It grew gradually from an empty house I had taken responsibility for, as I explored its potential and what was possible. At the same time, I was graduating from the Estonian Academy of Arts, transitioning from the structured environment of school to the uncertainty of life as a freelance artist. The museum became my personal survival strategy.

I was also influenced by my experiences of visiting traditional house museums, with their static displays of original objects. I wanted to ensure that no one would one day interpret my life in such a fixed way. The only solution was to take control and create my own museum while I was still alive – an unconventional approach, as house museums are typically established posthumously.

Today, Estonia has one of the highest numbers of museums per capita in Europe. People have turned almost anything into a museum, seeking to preserve and give meaning to their lives and surroundings.

Ah, I didn’t know this last fact about Estonia when it comes to museums… that’s so interesting. So even though the country is so much about innovation it also wants to conceal and keep things… I would love to ask you something that I have always been curious about since we first worked together, but maybe since I was so close to your practice, I did not have the time to reflect on it that much. I’ve always been deeply impressed by your ability to capture major societal themes within the smallest, most ordinary moments of everyday life. How does your process usually begin? Do you start by thinking about the big issues of today and then seek out traces of them in everyday life? Or is it the other way around? Does a small, everyday observation spark a deeper reflection on larger societal problems?

Small leads to big. Big shrinks to small. I often stumble upon themes by accident, improvising as I go. My process begins with small observations that gradually build into a larger narrative. In turn, big themes naturally find their way into my work.

Take Uprising, for example, a series centred on a video of roof repairs at my home. The discarded metal sheets became DIY-style planes, symbolising both military power and themes of escape, immigration, and borders. The exhibition, which includes video, drawings, and 3D models, reflects Estonia’s tense political climate – media-fuelled paranoia, defense funding debates, and NATO reliance in the face of Russia-West tensions. At first, I simply wanted to repurpose roofing metal in an interesting way. But then, Russian planes violated Estonian airspace, and the idea of transforming the metal into planes became a direct response to that.

The approach was different when working on an exhibition about violence against women. Having engaged with these issues for years, thanks to my mother’s influence, the process was much more deliberate and deeply researched. Yet, even in tackling such a heavy subject, my works maintain the same sense of lightness and humour that defines my practice.

If someone asked me to summarise your practice in one or two sentences, I think I would struggle, as your approach to art-making is so multifaceted as we learned now when you were talking about BANANA. You work across various media, from public performance to painting and drawing, incorporating ready-mades, staged photography, and film while collaborating with different social groups. As both an artist and a museum director, your work feels inherently democratic – not only in its deep engagement with real-life experiences but also in the way you treat materials and media as equally valuable tools for expressing concepts, ideas, and critiques. How would you define your practice, and how has it evolved over the years to become so multilayered? What influenced this expansion across different media and methods?

As a child, I practiced ballroom dancing, competing in ten classic styles – from the slow waltz to the jive. Then I made a complete U-turn, shifting to athletics, specifically the decathlon, which also required mastering a wide range of skills. Perhaps that’s where my love for diversity comes from. I quickly lose interest in sticking to just one technique or theme – I crave new challenges and variety. Rather than perfecting a single approach, I’m far more interested in generating fresh concepts. When I create, I don’t start by imagining how a work should look – I let the ideas lead the way.

Flo Kasearu’s solo exhibition BANANA – Build Absolutely Nothing Anywhere Near Anything is open at the Kai Art Centre in Tallinn until 3 August 2025.