Cultural anthropologist Stefan Helmreich has referred to the ocean as a hyper natural place, a nonhuman zone, at the same time acknowledging that human enterprise is thickly stirred into both the notion and the substance of the ocean as it is linked to human politics, economics and histories.

I have lived next to the Baltic Sea most of my life and have become acquainted with the local context over the years. In scale, the sea is different from the ocean and the Baltic Sea in particular is extremely vulnerable due to its size, low salinity and very narrow connection to the ocean. The ocean has, nevertheless, once been here, and left behind sediments over millions of years now part of the soil of the countries that surround it. For example, during the Ordovician period a set of mineral resources became part of Estonia’s now valuable sedimentary layer underneath the soil. Among others, oil shale was formed, deposited in a shallow marine basin. Around 40% of oil shale is made of organic substances, mainly algae and cyanobacteria. In Estonia, it is locally known as kukersite.

A year ago, we started a research project ASHTRADE with the materials studio Studio Aine. We looked into how these hills of waste, previously considered hazardous, are being reconsidered in light the development of carbon negative technologies that enable the extraction of minerals and metals from the ash, such as calcium carbonate or aluminium and more. At a time of a scarcity of global resources, these mountains may be envisioned as future currency, to be traded fraction by fraction, between industries that are in critical need of raw materials. We conducted a set of experiments with the material, forming tiles and vessels. These were empirical experiments that really emphasised the tiny scale of humans next to the man-made mountains resembling living organisms. We also made glass capsules for this future currency and prayer beads that could reveal themselves as depositories of future materials, awaiting to be unlocked in an alternative future.

These hilly landscapes are breathtakingly beautiful, yet eerie – the essence of the Anthropocene. The water around the area is blue and exotic, yet devoid of life. ”Should this artificial organism perhaps stay there and slowly decay as a rudiment of the present day”, we contemplated, while researching present and future scenarios for the place. I have often thought of this landscape as the embodiment of a narrative of material affairs – from seaweed to ash trade, the value and role of materials transforms over time. There is charm in this process, yet we are all aware of the urgency of a future that could be considered a symbiocene.

Seaweed Ceremony

There’s an interesting Estonian folk story that suggests that swimmers should leave their socks on when going into the water, or perhaps even two or three pairs because a mysterious mermaid might come and grab them by the foot – the mermaid is then left grasping the sock, while the swimmer escapes.

As part of the same project, students from the Iceland University of the Arts looked into the lives of algae and wrote: At the beginning of this project, we didn’t view algae as majestic, but rather as slimy, smelly, and uninteresting. After three months of traversing the world of algae, we’ve come to realise their innate beauty, opportunities and profound fragility. Our goal with the project is to encourage respect for algae. By exploring the realm of algae: getting to know their differences and embracing them, our hope is that with more knowledge and discourse, our coexistence can be strengthened. In the words of Guðmundur Páll Ólafsson, ”You protect only what you love, you love only what you know. You know only what you are taught.”

During this process, in order to get to know their research object, they created a piece called Resonance of Algae, where the marine plants were scanned and transferred to a sound synthesiser. The frequency of the sound decreases the deeper in the shore the algae lives. So, each algae becomes an instrument played by the sea.

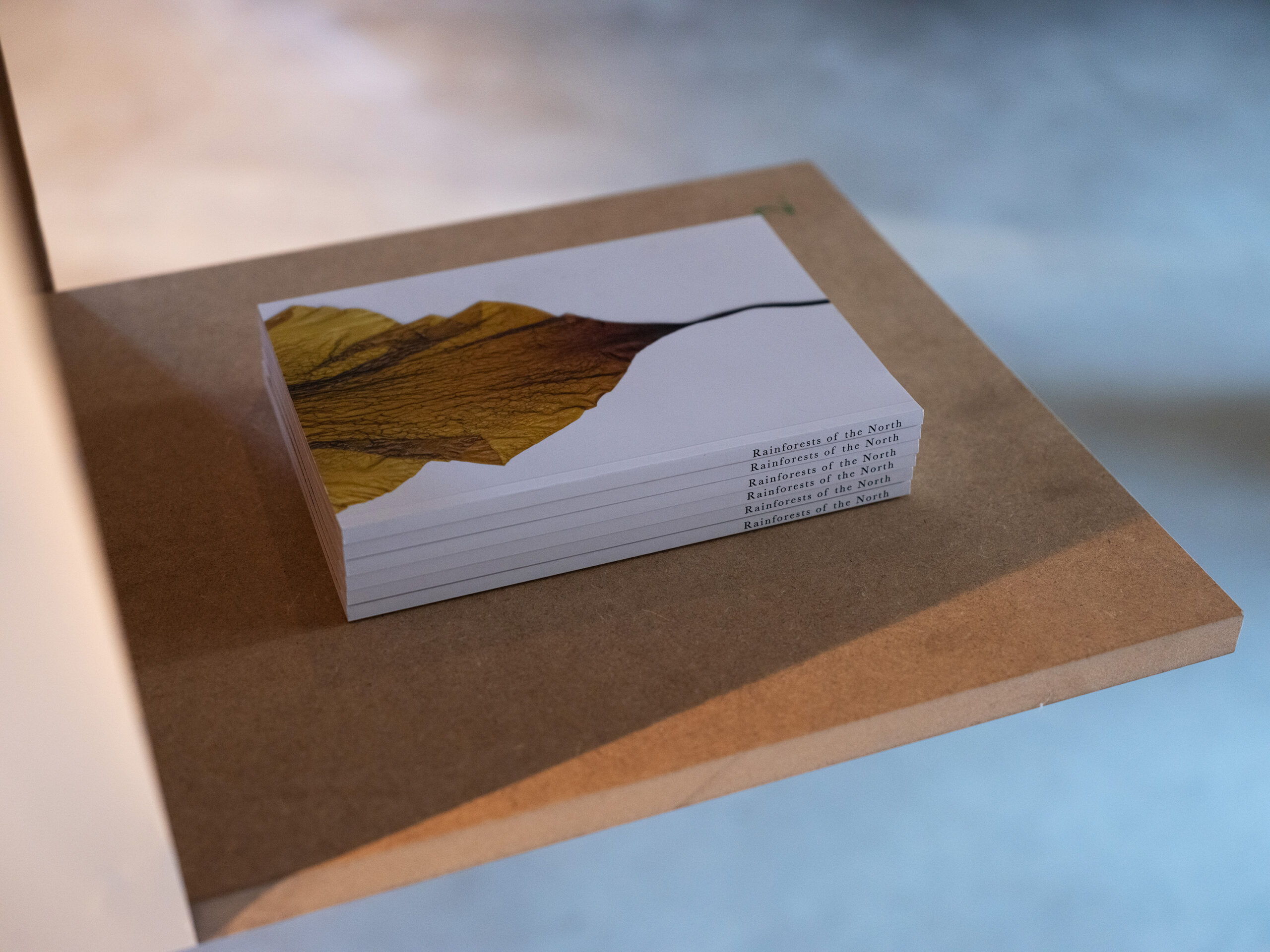

Tide Clock, an artwork from the research project The Rainforests of the North does not follow the traditional 24-hour day, but is affected by tidal range. The clock is connected to a specific shore and its water volume is controlled by the tides on that shore. By understanding the tides, it also becomes easier to understand when to seek the stray matter on the shore.

The Baltic Sea does not have tides, but we often walk its shores. A lot can be found there. Objects that are left behind when something is destroyed; broken objects that have been abandoned because of their uselessness; forgotten things; fragments of objects; objects expressing imperfection, temporality, incompleteness; objects whose meaning and physical form have changed.

Alongside man-made materials, biomass can be found on the shore as well. During the past five years we have carried out research with the students at the Estonian Academy of Arts, collecting seaweed and experimenting with the pigments and other substances that can be extracted from the plants. These seemingly unmodern techniques for creating pigments and printing pastes are an attempt to envision alternatives to artificial colourants. Additionally, a set of material experiments using local algae have been conducted, some of which are more anonymous-looking bioplastics and some that reveal where the material is sourced. These investigations along with a performance were shown at an exhibition called Seaweed Ceremony, an exposition and exploration dedicated to seaweed.

Metabolic craft

A few years ago, I was asked to contemplate the future in the context of the Estonian sea shore for the exhibition Leviathan: the Paljassaare Chapter at the Kai Art Center. I decided to speculate on a hypothetical community living next to the sea far away in the future. Inspired by local traditional knowledge and global mythologies around sea-related craft, I modified traditional objects, foreshadowing a speculative scenario, where future communities living near the sea use the resources available to them to delicately craft useful, and in some cases impractical, objects and materials. Each object questions the inherent value of materials, knowledge, and techniques, and the relationship between fragile ecosystems and human societies that are part of them.

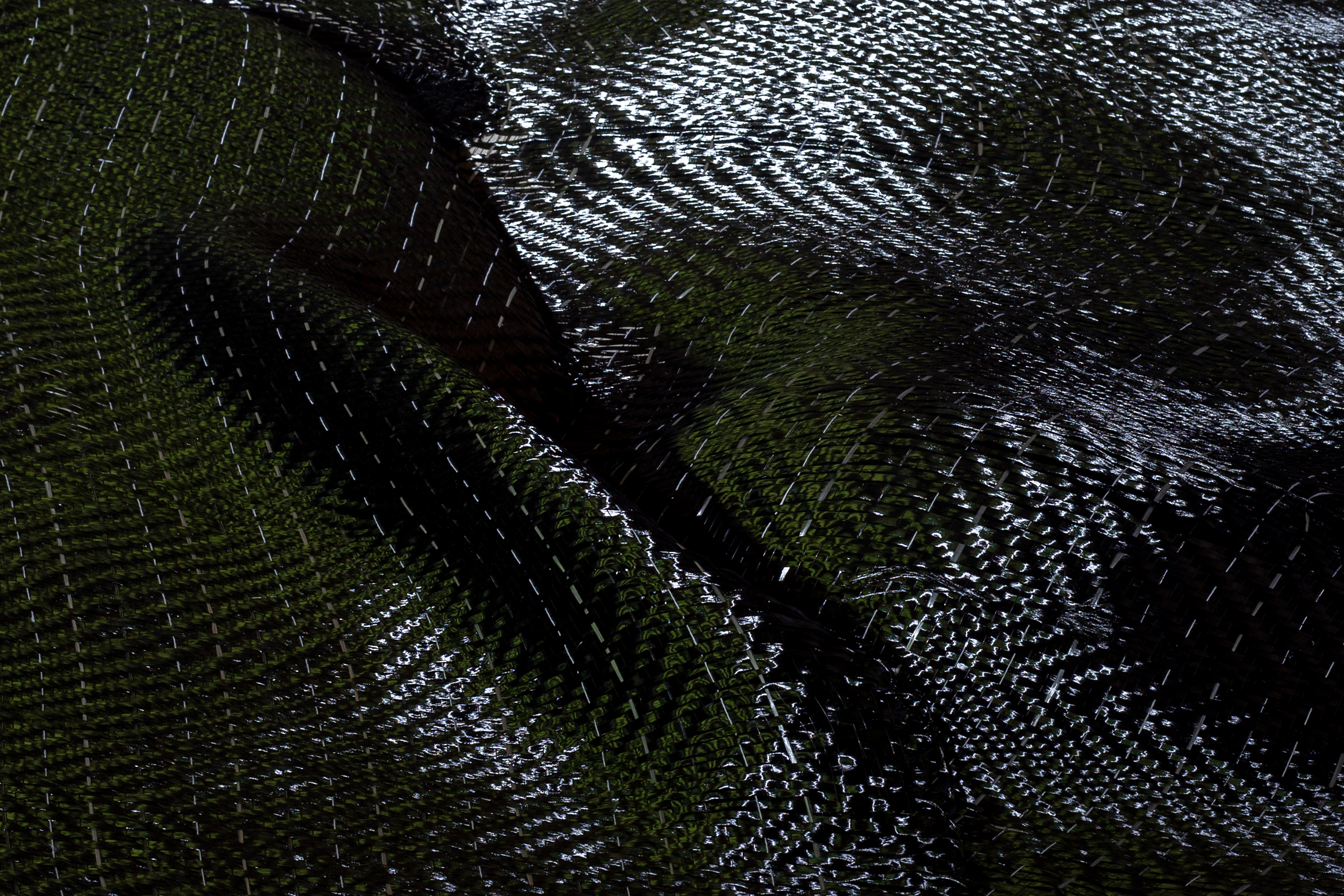

I started working on a sail. As goods were traded across the world, the history of sailing the seas is strongly connected to knowledge of materials and the technology for making durable sails. The outcome, a work titled Resting Sail is an inactive object, resisting an extractive mindset. Ancient and contemporary materials related to the sea or sailing are blended in this hand-woven fabric.

Next to the sail stood a hat, stewarding that new envisioned world as a ghost.

Dissolving Hat is made to last until it is exposed to water, after which it decays, leaving behind only the strings attached to it. The material, resembling leather, consists of crafted sea-sourced raw materials, which are highly prized in the food and medical industries. Its shape, combining that of a pirate hat and a fisherman’s hat, is practical, particularly at sea. This is an eco-luxury object with a predetermined shelf-life that perhaps shifts the focus away from mass-manufactured aesthetics to the irregularity of craft, looking simultaneously towards the past and the future.

Relaxing Mittens, positioned next to the hat, were tools for an invented ritual to be enacted somewhere between work and relaxation, forgetting and being present. Focusing on the hands, it emphasises the importance of these personal, highly-valuable working and communicating tools that enable us to perceive the surrounding environment through touch. Wearing the mittens means taking a rest, putting our hands on pause. This procedure is a tactile experience, as the material around the hands is living, breathing, and reacting, almost like a second skin. Due to the ingredients used in the material, the mittens have an effect at the molecular level.

Still engaged in the affairs of algae, I was on a short research trip to the Kristineberg Center for Marine Research and Innovation in September 2022, where the marine biologist Fredric Gröndahl kindly invited students and supervisors from Aalto University, Estonian Academy of Arts and Vilnius Art Academy to visit the community of marine biologists. The meeting was organised by Julia Lohmann, a renowned designer, creator and researcher, who has been working with seaweed for many years and who considers seaweed her material-method and muse.