...a small story opens up to become a more extensive one. A recount from a conversation sparked in passing, a tidbit of text, a flicker of video having already disappeared into the bottomless feed. Not much else is needed sometimes; I myself prefer such fragments that get stuck in my eye or my ear, tangled in my hair, like a flying seed carrying its plural story of origin.

This small wondering [here] sprouts not unlike such a seed, into the work of three Baltic women artists, Sandra Kosorotova, Anna Ceipe, and Marija Nemčenko, all of whom I had wonderfully different encounters with – full of exciting stories and tidbits – throughout the year. Their practices take root in the imaginaries of their regional landscapes and are migratory in and through them, along the poetic routes of vegetal ancestral drifts. The latter are not unlike what we call continental drifts; the processes of shifting, rotating, crashing, leaking, ripping and spurting that once broke up the Earth’s super-formations and created fragments now held together by intertwined flows.

Vegetal ancestral drifts – a mouthful but quite a useful formulation – appear in these artists’ practices as poignant critiques of the misarticulated myths of origin and belonging, of hindered motions and identities. Unbeknownst to each other, Marija Nemčenko and Sandra Kosorotova have been kindling a shared interest in fireweed – a fast-spreading, mid-summer-blooming, fluffy-seeded weed dubbed invasive. An intruder plant that feels comfortable in barren soil, made such by the promises of human progress – clanking industrial tools, laying railway tracks, spinning concrete mixers and oil barrels, hands sowing fire.

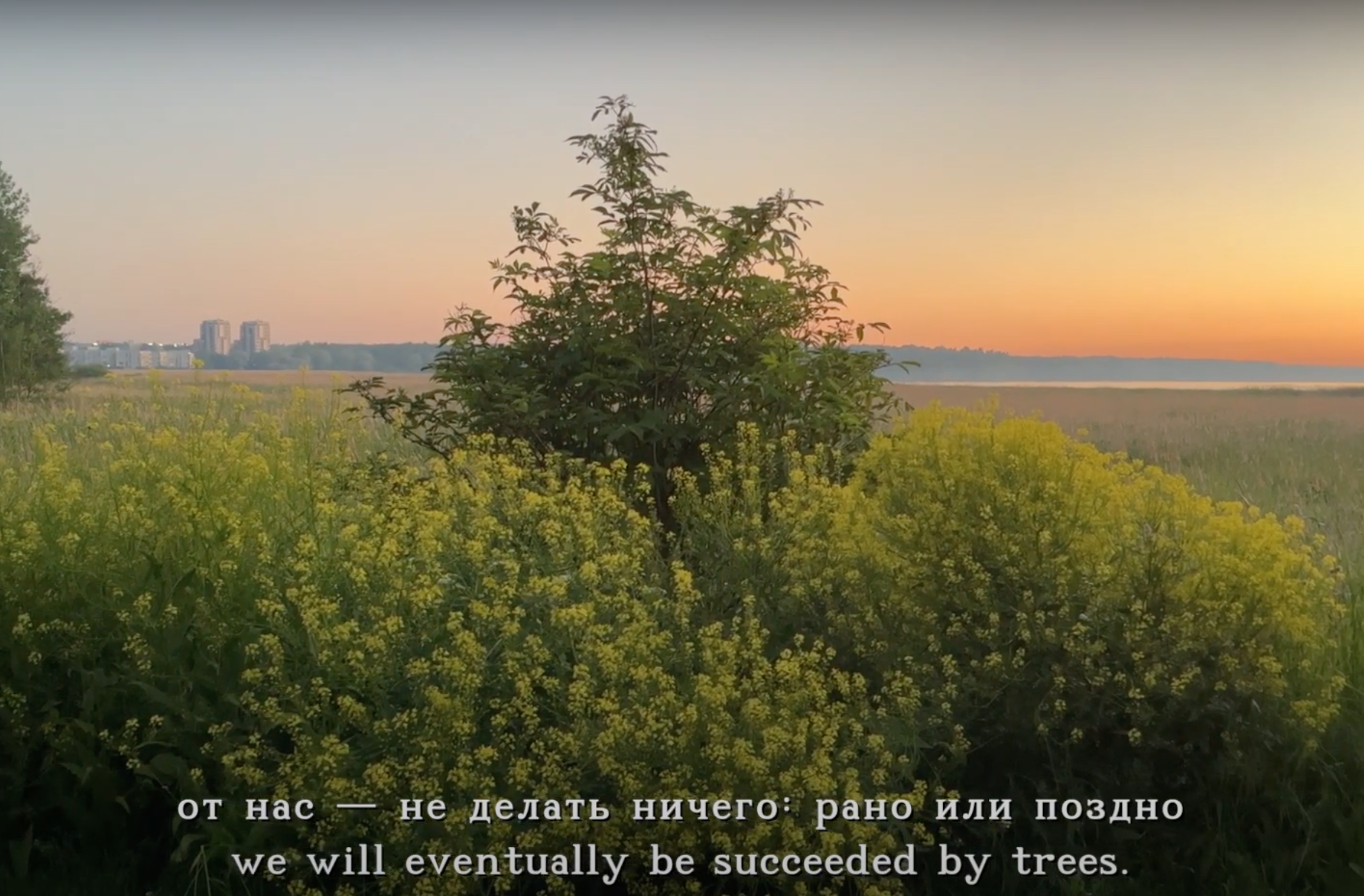

In her last exhibition In the Hands of Our Eclectic Physicians, which I curated this summer at the Swallow project space in Vilnius, Lithuania, Marija asked how curious it is for a plant to be placed in the pejorative human category of being invasive or alien; how to address the woes of a global agro-industrial complex (explored in objects resembling the architecture of local makeshift markets), and what would change if we stopped categorising non-human entities through human subjectivity and allowed them their own agency? This is a wide-reaching ontological question extending beyond this short text, but we could still ask it in such a way – how do plants become exposed to cultural conditioning, whether as a form of empowerment, or as a tool inscribing nation-state and identity politics?

Fireweed is placed exactly on this double-edged sword, as in the post-Soviet region it goes by another name – Ivan Chai, or Ivan’s tea in Russian. Its cultural properties have been accumulated and tooled to an extent that the Russian war-mongerer recently ordered the (Western) Coca-Cola production plants standing idle in Russia due to the company’s exit from the country, to be re-ignited for the mass-manufacture and dissemination of Ivan Chai.

Tallinn-based Sandra Kosorotova has been cultivating a similar albeit hyperlocal discussion of invasive and alien species, and differential cultural and geopolitical identities in Estonia, a country where no less than a third of the population, while being of multiple ethnicities and nationalities, is nevertheless Russian speaking. Fireweed has been deeply explored in her work as a plant unwelcome in native ecologies bringing with it forgotten healing and nutritional properties.

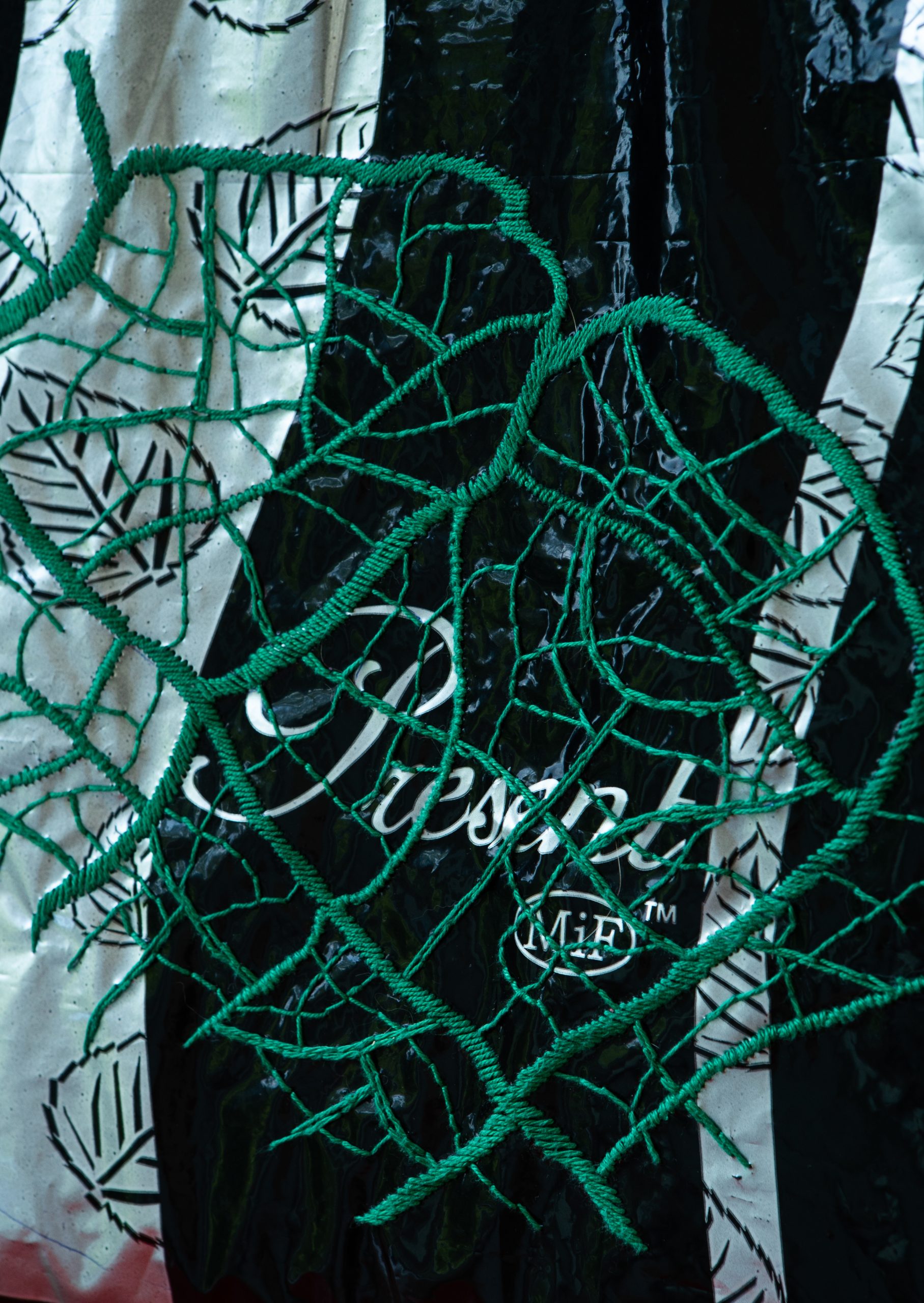

Sandra has recently expanded on this narrative in her short film Can I Grow Here exhibited at the Artishok Biennale in the Tallinn Botanic Gardens. The film is a three-language dialogue conducted in Estonian, Russian and English, involving bright yellow bushy weeds – colloquially known as Rakvere raibe or venekapsas in Estonian (Russian cabbage) – and the city’s most populous district of Lasnamäe, its resident majority speaking Russian and its landscape marked by socialist high-rise apartment blocks and chain link fences. A district segregated culturally and socioeconomically, Lasnamäe at some point in time lost its free access to the neighbouring botanical gardens (the very same) when a paywalled fence was built around it, which was not problematic to the same extent for the inhabitants of a neighbouring district of wealthier house owners. A garden guarding the exotic imported flora of the world and expelling the invasive Rakvere raibe and other uninvited guests. A microcosmos of disrupted belonging, of dis-belonging, of the troubled sense of a name when the world is swirling around.

What’s in a name, asks Sandra, ”a rose is a rose is a rose, a human, a plant, a monster or a plant-human?”, articulating the entangled nature of things and gesturing towards the cultural seeding of knowledge and its borders. What’s in a name, asks Marija of the invasive fireweed, weed-of-fire. What’s in a name, asks Latvian artist Anna Ceipe, who this autumn had an exhibition at Hoib gallery located in a basement in Tallinn. A curious arrangement of shipping and scenting devices, the exhibition traces stories of origin, from the intimate to the universalized. It studies the naming and archiving of flora or the science of classification that started with scribblings in the exotic journals of white men in the early 1800s. Coincidentally (but not really), as the voice in Sandra’s video tells us, the understanding of alien was introduced after the mid-18th century. Establishing the invasive other requires the original lines to be drawn, identities established and sealed. These become troubled when the Latvian Museum of Natural History is replenished with plant species from South Africa somehow found in Latvia. Could this be the work of some vegetal ancestral drift?

Anna’s exhibition, Notes from the Floating Ground, included a glass vessel crafted in the waning tradition of Soviet Latvian glass-blowing (a highly collectible craft, I was told), holding within itself the aroma of the Latvian seaside, where the artist’s grandparents reside. The scent of her grandmother’s spice trade with sailors, damp wooden ship boards, storage containers exchanging hands; there is no way of confirming the truthfulness of the aroma, an intimate and indescribable mixture of memories and myths.

The drifting vessels of origin collide and take shape, small stories become big ones and vice versa; the seeds keep tangling in your hair, sprouting anecdotes in imaginary landscapes.