At one point I started to make a mental note every time I saw yet another art book, exhibition, conference or talk on the topic of something (usually the whole world) in “crisis”. Although I might agree that crises are prevalent and probably expanding, is there any possibility of change if we get stuck in the same loop?

Working in the arts, we do, of course, need to be socially aware and there is a pressure to constantly have and express opinions. However, why is it that all exhibition texts and event invitations start to read the same? Are we all really thinking the same thoughts or are we just stuck using the same language? Curator Margit Säde describes below how she found countless mentions of the word “care” in her mailbox in just one month. Can we escape this vicious circle and develop more meaningful language?

We asked six artists, curators and writers from the Nordic-Baltic region what word or phrase they hope to never see, hear or read again on the art scene.

Maria Metsalu: Currently, I am busy with the temptation to call the new work a non-hierarchical exploration of companionship or something.

Embodied subjectivities. A work that comes with a dense explanation trying to convince you that me screaming at a pile of broken ceramics is a transgressive critique of capitalist temporality.

Acting like I'm unpacking the human condition but it’s a piano in a dimly lit room with a flower that probably needs water. That’s my liminal space, by the way.

I used to think liminal meant something mysterious and profound but now I think it's just bad lighting. Critical dialogue? "We had a chat." Not as intense as it sounds, I promise.

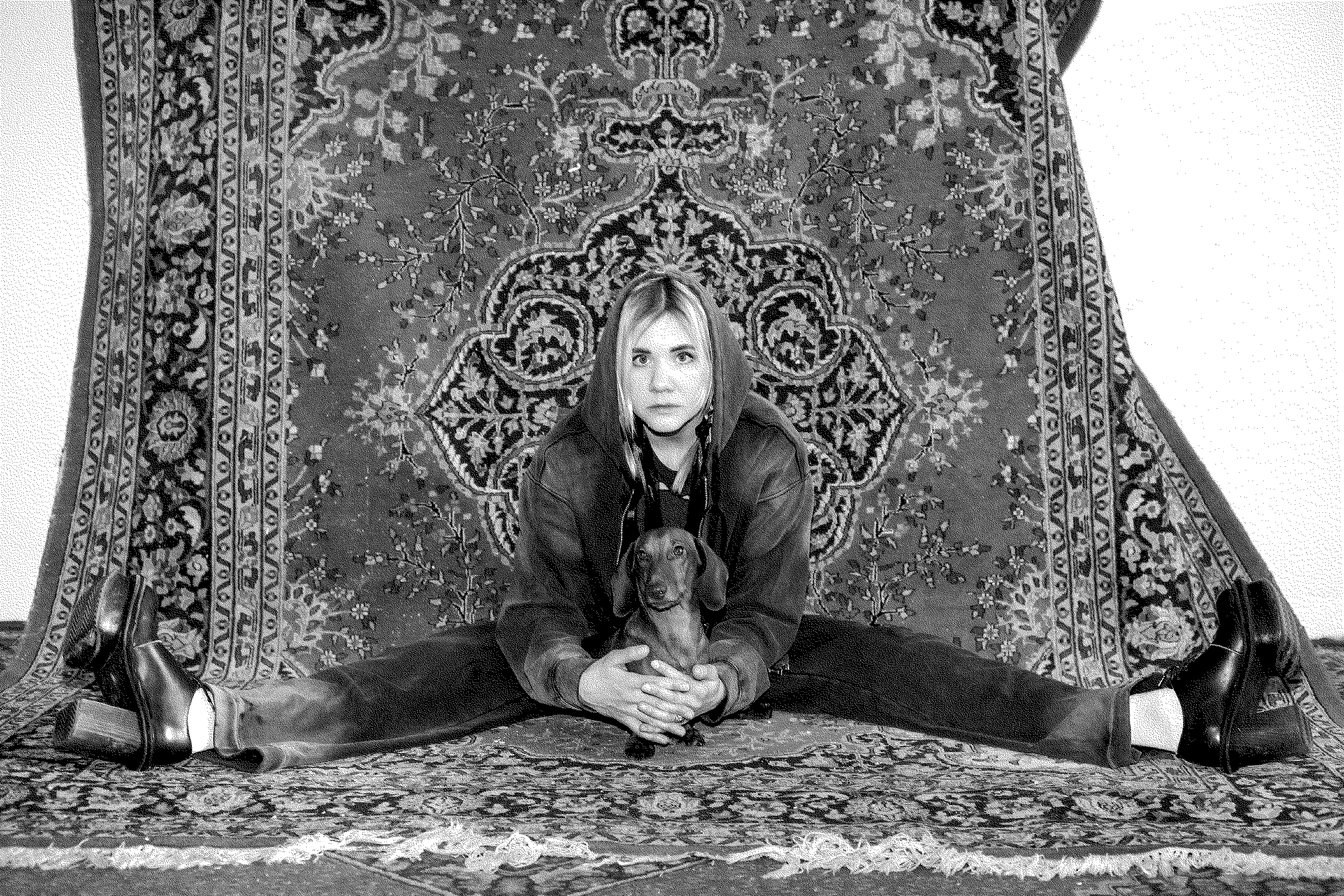

Non-hierarchical? The curator still picks who gets the best room. Augmented reality? I can't even deal with regular reality, let’s downgrade and pee on the floor a bit.Currently, I am busy with the temptation to call the new work a non-hierarchical exploration of companionship or something. But I think it's just me and my dog having a moment. No speculative futures or relational aesthetics – just pure chaos and maybe a dog.

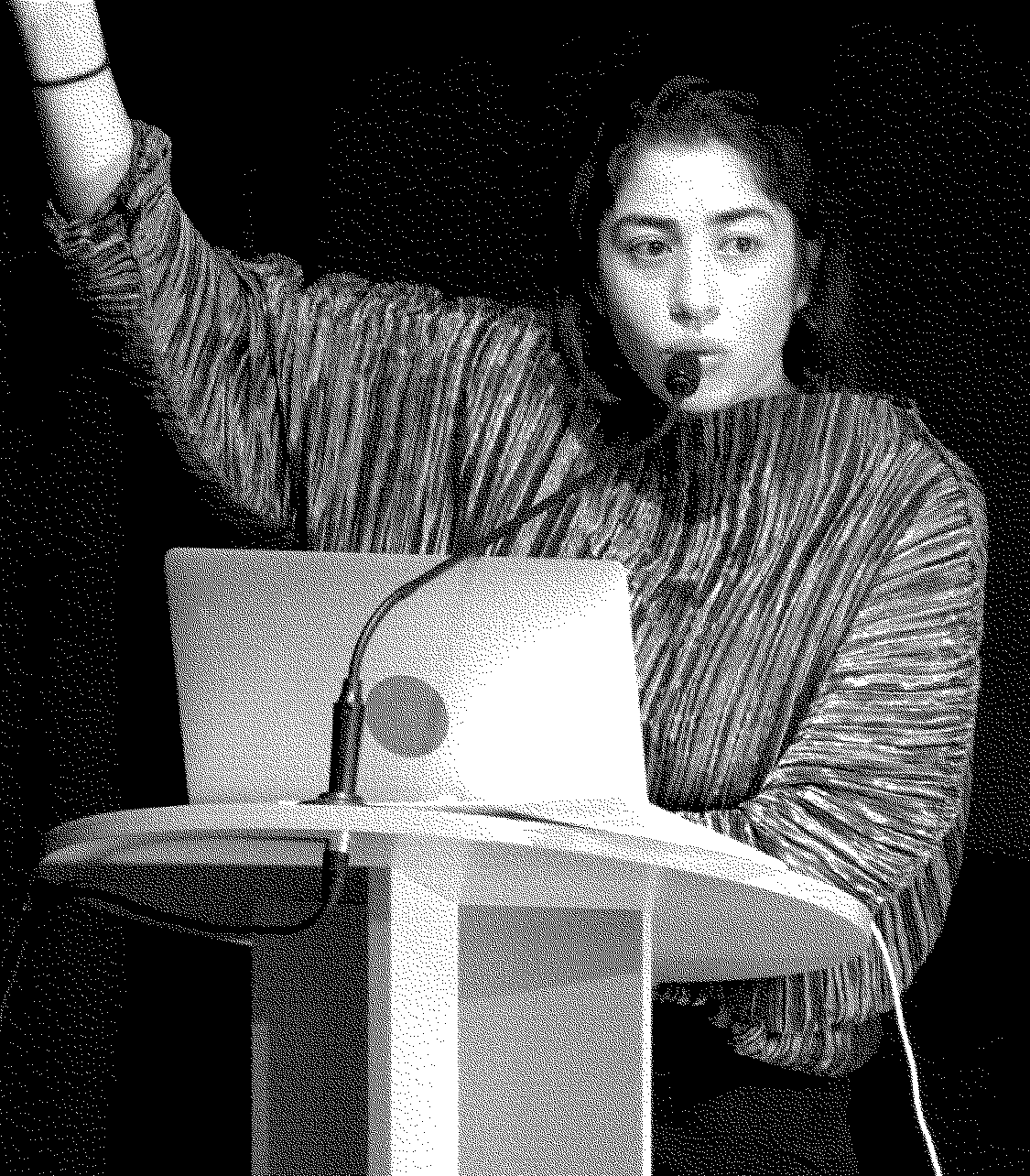

Mariam Elnozahy: I have come to hate the word decolonise.

I have come to hate the word decolonise. I specifically hate how it is used in art parlance. Decolonisation is not a metaphor. It does not take place in biennales, triennales, exhibition spaces, panel discussions, or VIP viewings. It happens through acts of militant resistance, legal repatriation, restitutions of land tenure rights. Last year, we saw acts of decolonisation taking place in Niamey, Gaza City, Jenin, Panama City, and across Mapuche lands from Bíobío to Los Lagos. Not Venice, London, Berlin, or New York.

I’m not trying to say that art is forever condemned to the realm of the symbolic. There have been countless examples across history to prove otherwise – just look at the work of New Red Order or Basel El Maqousi or Seba Calfuqueo or AZ OOR or Sinzo Aanza. To name a few. But to throw around the word decolonise so glibly detracts from the stakes at play in the act of decolonisation. The stakes are very very high.

Margit Säde: Yes, I know that curating comes from the Latin word cura (care! attention! concern!)

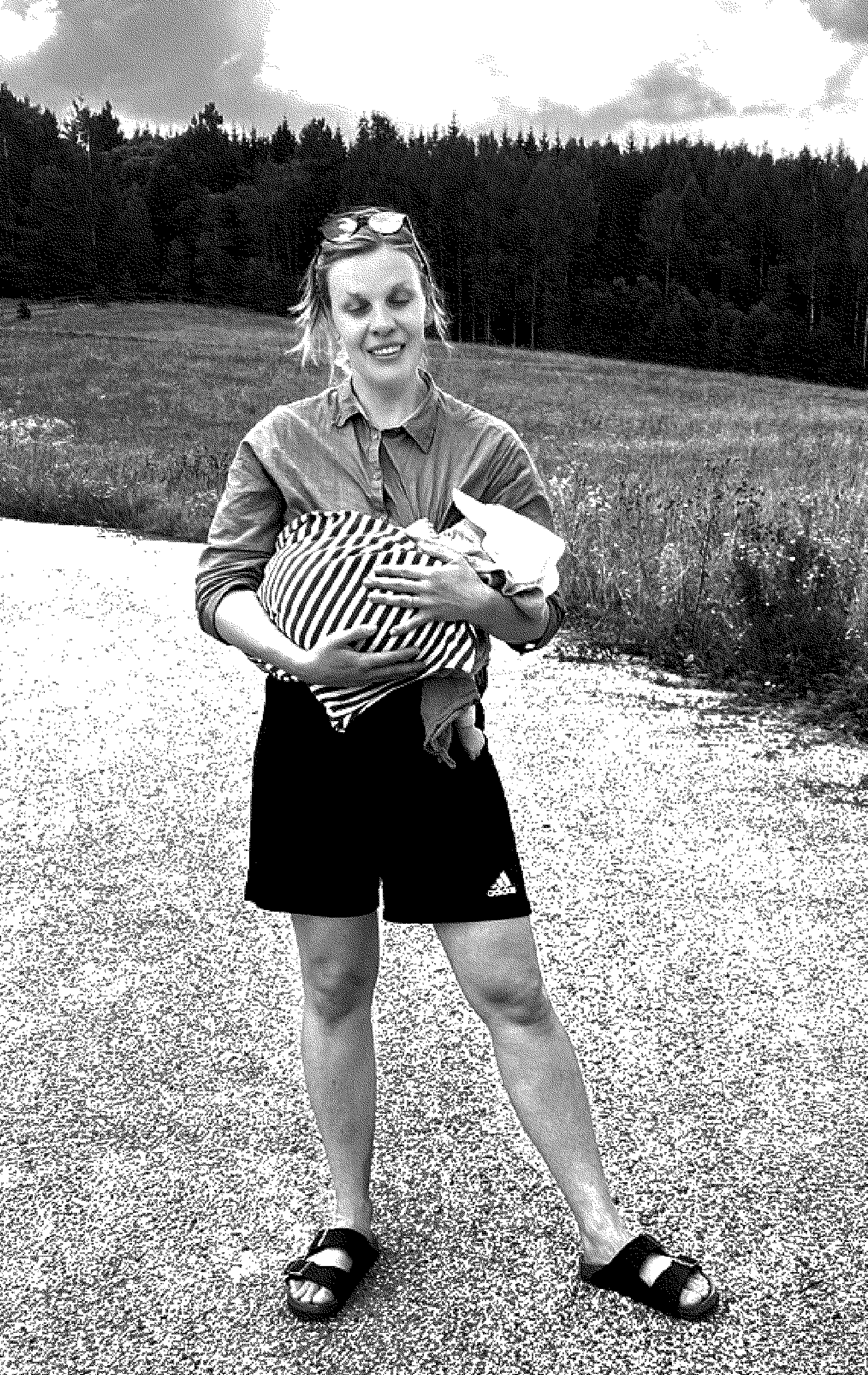

There is a word that has annoyed me in the context of contemporary art for a while due to its overuse – “care”. And now, due to changes in my personal life (I now have a baby!), to me, its meaning has been increasingly lost.

Yes, I know that curating comes from the Latin word cura (care! attention! concern!). When I quickly search my mailbox, I find that already this February (the shortest month of the year!) I have received countless newsletters, exhibition and events press releases that insist on the relevance of care and caring: curatorial care, collective care, feminist care, community care, collaboration as care, compassion and care, mutual care, radical care, spatial care, place of care, care in the time of darkness, deeply caring curators… In addition, there are commercial announcements, where words like post-partum care, vaginal care, baby care, self-care, skin care, body care are used to sell all kinds of products and services.

Eliminating my baby's rather large poop-explosion, I hum to myself "Let’s talk about care, baby…”, make my way through what only a few hours ago was my kitchen floor and humbly begin yet another round of breastfeeding. “Let’s talk about care!”

Both visible and invisible care and self-care are important themes and I'm not saying at all that these should not be addressed in the artworld but it's often the case that talking about care is a lot trendier and sexier than actually doing it. I'd like to hope that we are moving towards the kind of art world that not only talks about care but also practices it through its infrastructure and support systems.

Jaakko Pallasvuo: The art system would benefit from being more open to what artists find important, even if there doesn't seem to be any urgency to it.

The first thing that comes to my mind is the word “urgent.” I seem to remember a text that curator Anders Kreuger had written that critiqued the notion of urgency, but when I asked Anders if he could send the text to me, it turned out not to exist at all. Instead, my mind had elaborated on a short reference to urgency in a completely different text of his:

“Interest is grounded in an emotional conviction on the one hand and rational analysis on the other. It is slower and more thoughtful than, for instance, “enthusiasm” or “urgency”. Therefore, it is more sustainable and less prone to political and managerial mood-swings.”

When something is defined as urgent, it often feels like a managerial gesture: funding bodies or biennial curators expecting adherence to a certain order of priorities. Urgency requires a consensus on what is important. It's not a matter of artistic importance or personal importance, but an echo of political discourse and what dominates the news cycle at a given moment.

An echo is a reaction. The urgent is reactive. Urgency relates to emails, deadlines, planetary crises and teeth grinding. Urgent temporality is anxious and chronically stressed out. The urgent shortcuts thought. Something must be done. I should be doing something. Now!

In a chat, Anders writes: “One more thing about the urgent. When you say something is urgent, that shows you're already too late, that you have allowed the topic to overtake you…”

I think the art system would benefit from being more open to what artists find important, even if there doesn't seem to be any urgency to it. I'd like to see art move from the silo of the urgent to a kind of gestational darkness, where meaning could be built up in longer strands.

I don't think of urgency and slowness as opposites, though. I amuse myself by thinking of non-urgent speed: a dog chasing a frisbee or its own tail. I'm thinking of frantic, self-initiated activity with no reason or justification. I'm thinking about degrees of freedom.

Krista Kodres: I would like to go back to the point, where "monumental works" could be celebrated as tools of remembering and memory

A word I think should be forgotten for a while or at least be redefined is "monument". Why? Because it is mainly associated with the so-called monument wars that has gained ground in recent decades. On the one hand, this testifies to the fact that the magic belief in the power of images is very much alive today and on the other, provides possibilities to politically manipulate with meaning.

In Estonia, there’s currently a war against Soviet period monuments. We really should remember the origins of the word "monument". It comes from the Latin word "moneo", which means to "remind" or "warn" and its contemporary meaning – "burial site marker". In many languages, through the long history of Western culture, the term "monument" has acquired an additional meaning, linking it to emperors or those whom history should seemingly hold in particularly high honour, the so-called Great Men of History.

I would like to go back to the point, where "monumental works" could be celebrated according to the original meaning, as tools of remembering and memory. There is another word for such works, which for some reason is often forgotten – memorial. Significant historical events are not always great but can also be foolish and painful. We also need to understand and remember those, and this is precisely what memorials can help us with.

Elīna Ķempele: Reading, hearing or seeing something that makes your eyebrows rise or your blood boil is unavoidable

With the overwhelming amount of information we choose and are forced to consume daily, especially in the current heated atmosphere, reading, hearing or seeing something that makes your eyebrows rise or your blood boil is unavoidable both in the art scene and beyond.

However, it’s hard to remember and point out one particular word or phrase to be shunned forever, especially since the meanings and messages they convey mostly lie within the context.

It would be easier to think of attitudes or actions. One rather trivial phrase though comes to my mind – “That’s not art!”. Such a verdict recently dominated the comments on news portals and social media posts in connection with the supposedly controversial creative expressions of Latvian artist Kristians Brekte. Nothing new. I have heard this phrase so many times, targeting particular art works, artists or contemporary art in general.The discussion of what is and is not art, and why, can be very stimulating, yet it is a sad dead end if the only argument is I don’t like/understand it. I will repeat myself – there is nothing new and particularly noteworthy in this, and yet, I get triggered every time. Such statements are not only expressions of a personal opinion but are often used (with an ideological and political motivation) as a good enough argument to control and limit not only artistic freedom and funding, but also freedom of speech and ideas.