On 24 February, Estonia celebrates its day of independence, so in the morning of this public holiday in 2022, I opened my iPhone, expecting to find a boring festive news stream about the President’s speech and galleries with images of the traditional raising of the flag at sunrise. Instead, in shock, I stared at the news of the Russian army invading Ukraine and explosions in Kyiv. I believe that the meaning of this otherwise standardised national holiday probably shifted radically for most Estonians. However, in the following days, weeks and, by now, a whole year, the question of how to go on with our daily and professional lives, how to make artworks, curate shows, write art criticism as we are witnessing horrific events became very relevant.

So I asked curators and artists from Estonia, Latvia, Ukraine, Poland, Finland, Norway and the USA to reflect on how they have dealt with the same questions: How has the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine changed their ways of working and thinking, both in the practical and theoretical sense? How has the (art)world changed?

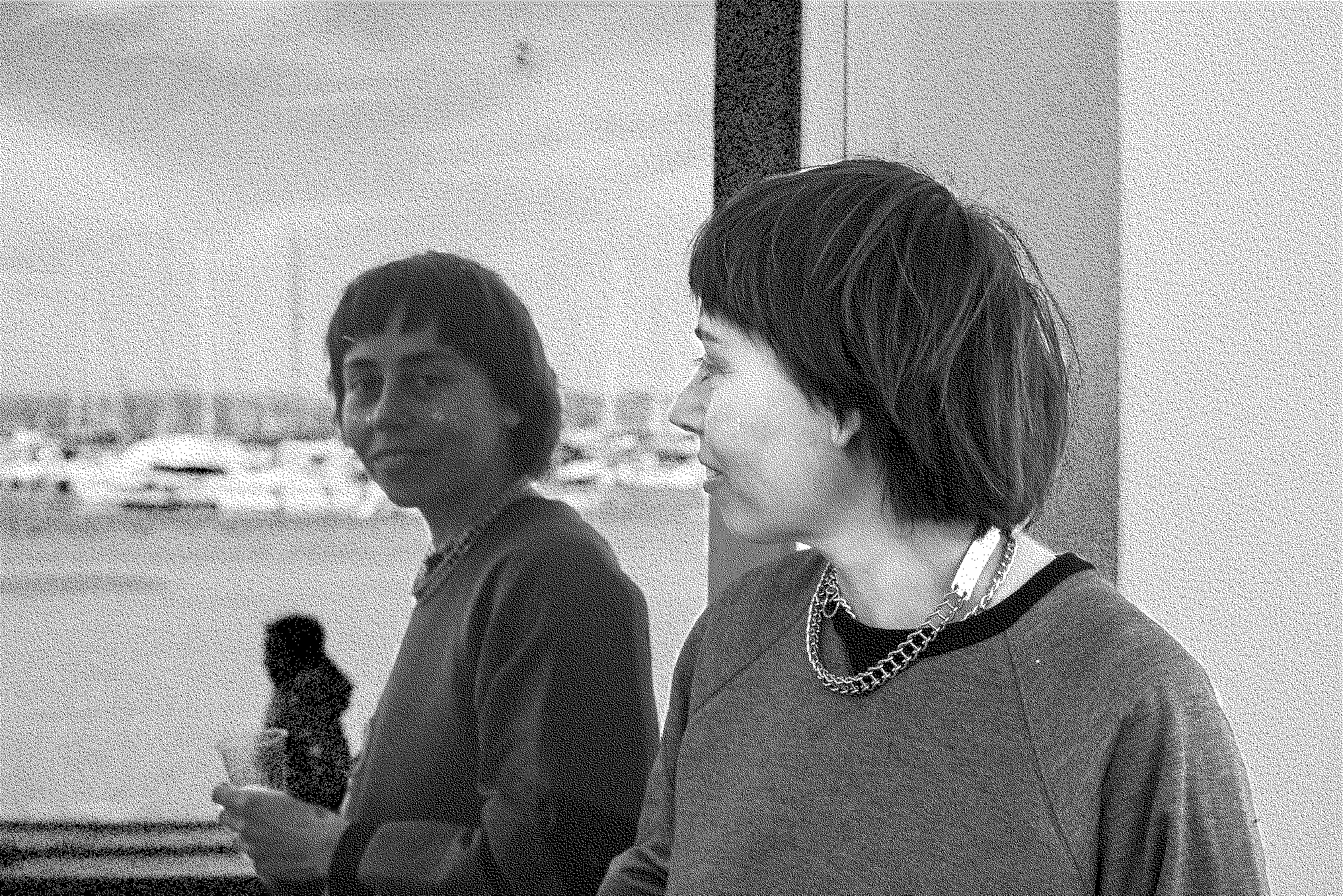

Zhanna Kadyrova: I remember how my creative life of 20 years seemed like a dream

Zhanna Kadyrova is a Ukrainian artist who has participated in numerous international exhibitions, including the 58th, 56th (international exhibition) and 55th (Ukrainian Pavilion) Venice Biennales, and the 2017 Kyiv Biennale. In 2022, she started the project Palianytsia as both an art and fundraising project.

On 24 February, I was in my home in Kyiv when I woke to the sound of bombing. My brain – the brain of a person raised in a civilised world – blocked me from fully understanding what was happening and kept playing tricks on me. We thought it would all end tomorrow, the following day, we thought it would end the day after, then on 1 March, on 8 March, in summer, before the New Year. Now I am trying to adapt to the information available and understand that it will not end soon, the consequences will be horrifying and the trauma incredibly deep-rooted. And nothing will ever be the same.

In the second week of the war, our whole family decided to leave Kyiv. My sister took our parents with her to Germany, and it was only after that that I started to look for a new place to live and a new job. Having ended up in the Zakarpattia oblast, it took me five days to find a place – around six million internally displaced people from the eastern and northern parts of the country had moved to western Ukraine. I could think about art again only after my mother had safely reached Germany. Before that, art seemed like an ephemeral formation of the civilised world, something of an illusion and not relevant in the context of the war tearing apart the lives and fates of thousands of people. I remember how at that moment my creative life of 20 years seemed like a dream.

But a new life needed to begin and in this life benefiting those who are suffering and the army that protects us must be the priority. I wanted to come up with something I could make with minimal means, without a studio and sell online. This is how the project Паляниця was born (palianytsia is a type of Ukrainian bread) and so far, we have managed to raise over 200,000 euros for the army and the victims of the war. Necessary items are bought by my friends, who have become volunteers and soldiers; visiting the war zone was a completely new experience for me. Transporting cars to the front line, we reached the places the army is located, which are off-limits to civilians.

Several of my 2022 projects were created in connection to these trips. I put all the projects and exhibitions I had planned before the war on hold, except for those where the curators were willing to change the theme of the project to reflect the urgency I was now dealing with. In addition, my gallery Continua announced a moratorium on the sales of works that do not relate to the current situation in Ukraine. I consider it my mission to disseminate information about what is happening, as I am a witness to these events.

Generally, it is difficult to make plans and I find it hard to distance myself from the situation and start theorising about it, since the war is still being waged and I am in Kyiv.

Tanel Rander: It is the feeling of contamination that makes you want to vomit out everything relating to the abuser

Tanel Rander is an artist, curator and art writer from Estonia, who has dealt with Eastern European identity and decoloniality for years. At the moment, he is focusing on unlearning all of this and while not abandoning all of his past practice, he is now interested issues of mental health and individuation.

Regarding the art world, there is a kind of renaissance taking place in Ukraine and in the Ukrainian diaspora. The war has awakened archetypes in the collective consciousness of Europe. There is no better example of it than the works of the artist Kateryna Lysovenko.

Also, there is the great wash-off of everything that we used to know as Eastern Europe. The term now evokes being stuck in the past and holding too much encrypted and latent Russian imperialism that suddenly has become a weapon. I’m glad I never bought the idea of ‘the New East’ – I only ever saw it as form without content, based on the fetishisation of Soviet culture, especially its darker side. I also now believe that the ‘decolonial turn’, the one that departed from the Global South and involved anti-Western sentiment, was either influenced by Russian soft power or just instrumentalised and weaponised by its propaganda. When the war started, I was really shocked to see certain authors I had followed and respected, acting like Russian trolls. After all, the movement of decoloniality always included heavy anti-Western sentiment, self-victimisation and preaching the emergence of the BRICS countries. Around ten years ago that was all very compelling and catchy.

Now, the war launched me into a personal crisis of self-blame. I started to think that by having worked with East European identity and decoloniality for years, I was one among thousands, who were gentrifying an evil and cynical project of a few dictators. Who would have thought that my worst fears about Russia were going to come true?! Until then, I had been freely playing and joking around about Russian issues and its leaders, I had been openly nostalgic about my childhood in the Soviet era, I had been talking about the acceptance of our life, culture and history under occupation. It was all based on a kind of trust and feeling of safety that makes freedom possible. But that trust was abused. And self-blame is the consequence of abuse. It is the feeling of contamination that makes you want to vomit out everything relating to the abuser. Starting with Dostoevsky. Millions of people are going through this – feeling contaminated. It may seem like destruction, perhaps also self-destruction, but I believe that things will be sorted out and this may lead to a serious decolonisation of Russian imperialism. A huge constellation has broken down. It is not just about Russia, it is also about us, about Europe, etc. Especially now it is unwise and dangerous to keep calling ourselves Eastern Europe or the New East. Everybody knows who is playing the East-West game. But not everybody knows that we are the New West. Anyway, I hope to see the day when ‘geopolitics’ is added to the list of ideological crimes.

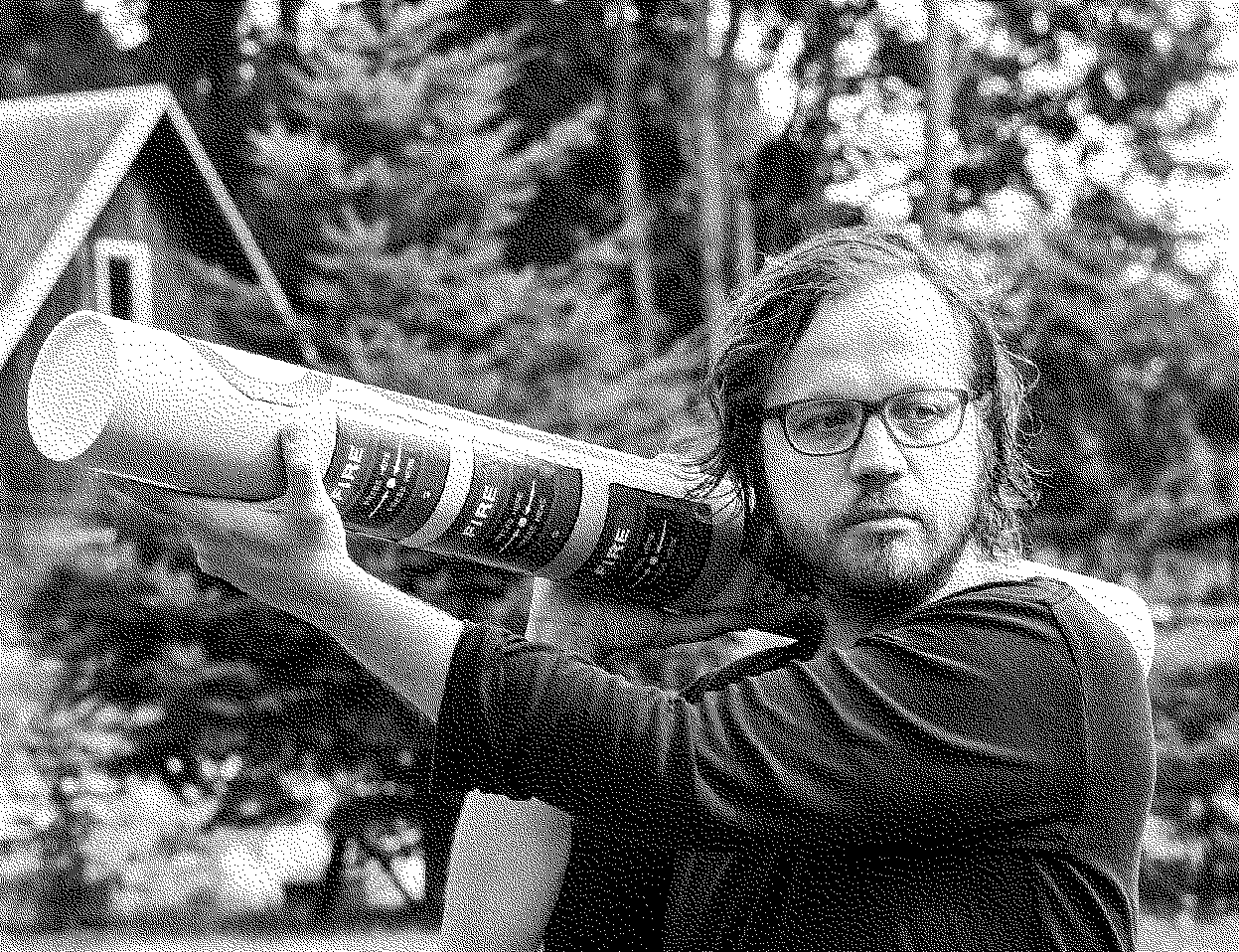

Sebastian Cichocki: It might have been the climax of my art worker’s life – dancing, reading and writing poems, eating, crying, and being in this shit together

Sebastian Cichocki is the Chief Curator at the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw. He is the curator of the 40th EVA International – Ireland’s Biennial of Contemporary Art, 2023.

In the recent past, I was involved in many discussions and public programmes, analysing the legacy of ‘solidarity museums’, these rare and precious moments when art institutions become something else: a hospital, food bank, playground, refugee centre. Think about Malmö Konstmuseum, which in 1945 opened its doors to women from liberated concentration camps, who slept, cooked, and even did art therapy there. When the Russian invasion started in Ukraine – my young climate activist friends immediately labelled it as “the first global fossil-fuel-fascist war” – all these lessons from the past had to be taken seriously. But such an institutional metamorphosis cannot always be planned and calculated in advance.

The Sunflower, the Ukrainian solidarity cultural centre at the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw, was indeed born quite organically. It was a safe but rebellious space, a harbour for refugees, queer kids, families with their pets (dogs, cats, parrots and hamsters were also looking for a refuge) and feminist antifa comrades. The Sunflower, initiated by a group of Ukrainian artists and poets called Blyzkist, collected funds for food, medical and hygiene products, electricity generators, as well as working with Warsaw collectives employing migrants and refugees, such as the Conflict Kitchen and Right Food. It wasn’t an art project but a rapture in institutional life. Not a public programme, but a gentle occupation. It might've been the climax of my art worker’s life – dancing, reading and writing poems, eating, crying, and being in this shit together.

Neal Cahoon: The theme of the Barents Spektakel festival 2022 Where Do We Go from Here? suddenly gained a new context

Neal Cahoon is a Northern Irish writer and curator based in Kirkenes, Norway. He has been leading the curatorial team at Pikene på Broen since May 2020.

There has been a fundamental change, not only in how the work of the collective Pikene på Broen is received in the art world, but also how our work takes place in Kirkenes. We are located 50 km from the Finnish Border, and 10 km from the Russian border. We live and work within Sápmi, the indigenous land of this region, in the Paaččjok sijjd, which is the rightful territory of the Skolt Sámi community.

Pikene has been working with collaborating partners in the cultural field on the Russian side of the border since 1996, and some of our core principles have been to promote dialogue, understanding, and freedom of expression through art. There have also been challenges in the past with this type of cross-border work, but the timing of the invasion in 2022 was particularly striking because it took place the day after we opened the festival Barents Spektakel and these events had a very strong effect on the entire programme. Our theme last year was Where Do We Go from Here? which suddenly gained a new context.

After the war broke out, there was a lot of discussion and action in Norway and other European countries about cultural boycotts of Russian art and artists, which was justified in some cases. But through our close dialogue with our collaborating partners, it was clear that the picture was much more nuanced and complex, and as a cultural organisation we felt it was important to support independent and pro-democratic voices in Russia, as well as sending a strong message condemning the war in Ukraine. Pikene now maintains contact only with independent cultural actors from the Barents region in Russia, many of whom have now fled the country.

One example was the attention we received through one project during the finissage of the last festival. Two Sides of the River was imagined by artists Tine Surel Lange and Pavlo Grazhdanskij as a gesture of analogue communication in an age of pandemic travel restrictions. The artists aimed to send real-life sound signals to each other across the border in the Pasvik valley. However, just one hour before the performance was due to take place, Grazhdanskij got the message from authorities in Nikel (Russia) that his permission to perform had been revoked due to the risk of a ‘snow storm’. On the Norwegian side, at 15:30, Tine Surel Lange stuck to the timeline, shifting between moments when she could send signals of a sampled foghorn from Lofoten across the border, and moments spent waiting in silence for a reply that she knew would never come. On the Russian side, the signals were heard by a small audience who had gathered to witness the work, and who also tried in vain to shout back in response. Although only 10 km away, on this occasion the distance was too great for the human voice.

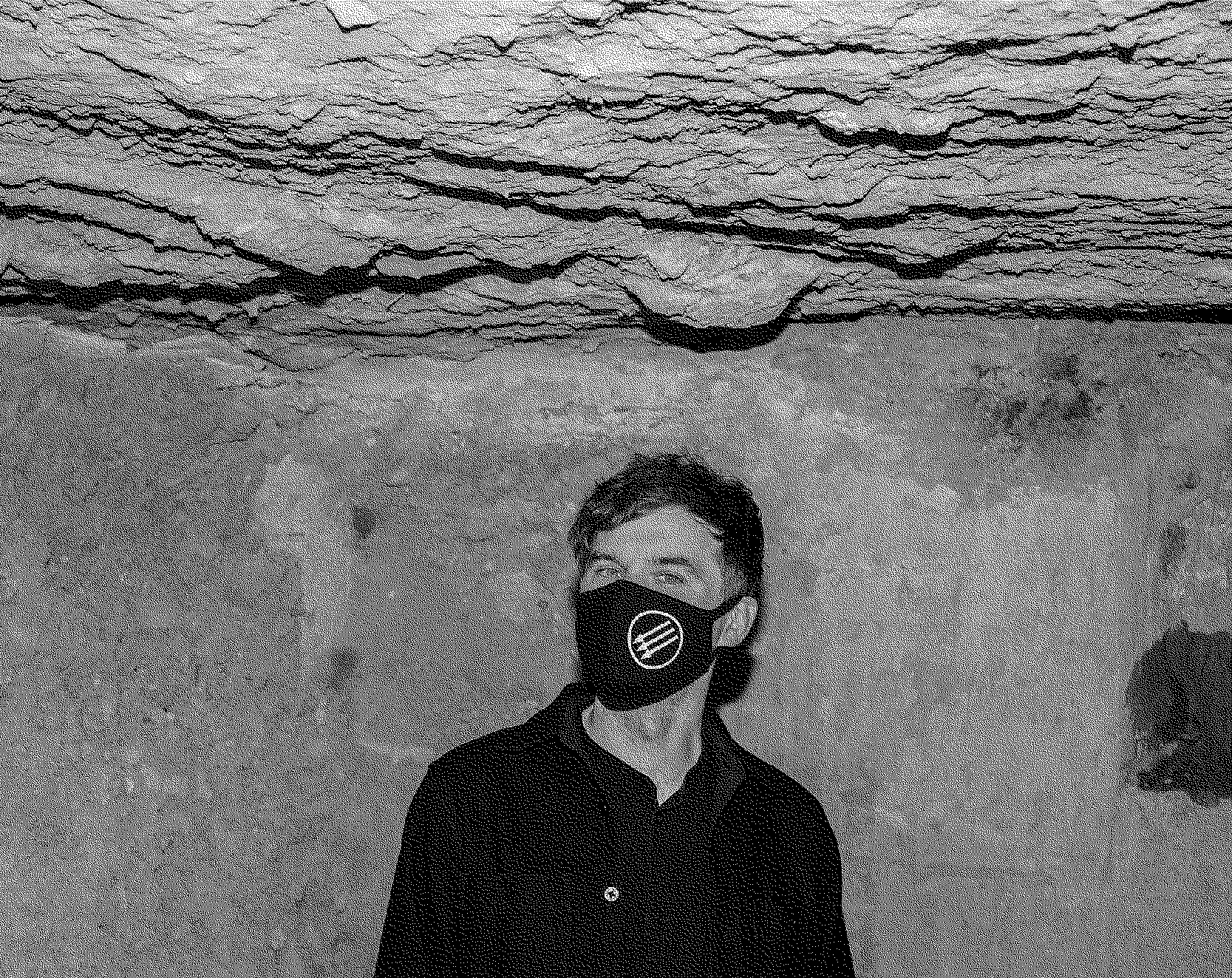

Dieter Roelstraete: The Russian invasion of Ukraine has robbed the world of a vast realm of cultural possibilities

Dieter Roelstraete is the curator at Neubauer Collegium for Culture and Society at the University of Chicago. He previously served on the curatorial team that organized documenta 14 in Kassel, Germany, and Athens, Greece. Recent projects include exhibitions at the Fondazione Prada in Milan and Venice, the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw, and the Garage Museum for Contemporary Art in Moscow. Roelstraete, who was trained as a philosopher at the University of Ghent, has published extensively on contemporary art and related philosophical issues.

There is no denying that the (art) world has changed dramatically since the beginning of the Russian invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022 – for the worse. Speaking as someone who long thought of himself as an incurable Russophile – and who, in that capacity, has travelled and worked in Russia on numerous occasions, in places as far apart as Moscow and Vladivostok, the Chelyabinsk Oblast and Ulan-Ude – the war has achieved the previously inconceivable effect of completely obliterating my enthusiasm for anything Russian. I haven’t read a Russian book in a year; I haven’t listened to any Russian music in a year; I haven’t watched a Russian movie in a year; I haven’t seriously looked at Russian art in a year – and I honestly don’t think I’ll ever go back to Russia either. (I don’t want to.) I have, in short, been cured of this seemingly incurable Russophilia. (And it’s not like I’ve become more pronouncedly Ukrainophile in the process.) This may sound like a petty personal anecdote but it isn’t – the Russian invasion of Ukraine has basically robbed the world of a vast realm of cultural possibilities, and the world is a much poorer place because of it. PUTIN MUST GO.

Solvita Krese: The war in Ukraine has introduced bold corrections in the writing of history, significantly affecting the art world

Solvita Krese lives in Riga and is a curator and director of the Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art (LCCA) since 2000. She has been curator and co-curator of number of large-scale international exhibitions, among these the Latvian Pavilion at the 59th Venice Biennale (2022). In 2009, she initiated the annual Contemporary Art Festival Survival Kit, which she curated and co-curated until 2019.

I assume that for many people in the Baltic region, their understanding of the world and their value system was shaken to the foundations on the morning of 24 February 2022. The war in Ukraine has fundamentally changed our worldview and has also had a significant impact on the art world.

When the war started, we at the Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art radically transformed our programme in response to the events in Ukraine. For example, in the exhibition space of the Museum of Medicine, opposite the Russian Embassy and the main protest site, we launched the Protest Workshop. There, together with artists and inhabitants and guests of Riga, we prepared posters and other visual materials for the protesters every day.

The war in Ukraine and the issues it raised were interwoven in all our projects throughout the year. It was present in the numerous webinars on decolonisation, where Ukrainian artists, curators and researchers were invited to participate. At the festival Survival Kit we created a special programme for Ukrainian refugees, The Hearing Voices Café, in collaboration with artist Dora Garcia. In the exhibition Decolonial Ecologies, a video by Ukrainian artist Olia Mykhailiuk was the central piece, accompanied by the premiere of her film Iripna, finally edited in Latvia, and a special performative programme with the participation of Ukrainian artists.

Close cooperation was established with the Kyiv Biennial through the development of various programmes within the activities of the East Europe Biennial Alliance. The war in Ukraine has introduced bold corrections in the writing of history, significantly affecting the art world, raising the relevance of the postcolonial discourse in the context of the region and highlighting the acute need for a process of decolonisation.

Miina Hujala: We need to understand the importance of being able to draw the lines, even if only temporarily

Miina Hujala is an artist and a curator, working as the director of the Alkovi art space as well as the curator of the Connecting Points programme at HIAP (Helsinki International Artist Programme). She is an artistic researcher and project manager on the Reside/Sustain-project that started in 2021.

After the start of the invasion in Ukraine in February 2022, I felt that war with its destructive violence that became real in Ukraine made the threat more pronounced also in Finland. I had been working with Russian artists, mainly organising residencies and exhibitions with them in the framework of the Connecting Points programme in the residency organisation HIAP (Helsinki International Artist Programme) from 2016. I had been somewhat safeguarded from a straightforward exposure to the harshness of the Russian regime, as I didn’t have to work with state institutions, nor deal with issues related to administration directly, but I had no illusions and no problem in understanding that anything is possible from the current regime. I had been following the situation from the side lines, so to speak. After the attack, the dependency of Europe on Russian natural resources, especially in the energy sector, became very visible. It has been noted before those deep-rooted issues within Russian society – like the narrow role of civil society or unreliable justice system – have often been overlooked, but now the concessions that have been and are being made to accommodate trade are taken a bit more seriously. Unfortunately, the ethical dimension is still often neglected.

For me, it’s important to emphasise that people are not their passports. After the Russian invasion, withdrawing from working with institutions in Russia has been the most direct result in my professional life and this also meant adjusting and rearranging projects that I was working with. More specifically, not travelling to Russia meant that, for instance, a project dealing with land-based methods of travel and that aimed at utilising the Trans-Siberian route to travel east had to be re-routed. I feel that diplomacy always has its power, but there is no sense in aiming to continue things as they were. Although maintaining contacts and connections is crucial. At HIAP (but also through a wider network), directing support to Ukrainians in the form of Ukraine Solidarity Residencies has been one of the ways to offer aid.

Finding ways to address the situation and how to continue have been at the forefront. I visited Tallinn after the invasion took place in early March 2022. I felt I needed some breathing space. As Vabaduse väljak (Freedom square) was basking in the direct late winter/early spring sunlight, I texted with my Russian colleagues from a recently started project called Reside/Sustain that addresses art residencies and sustainability. I stated that unpredictability had become more acutely present. I felt sad, as so many have tried to enable contacts and connectivity between people to lessen or dilute any harsh sentiments and antagonism. My projects are all about making discoveries, and allowing the versatility of perspectives to manifest is crucial. I bought Maggie Nelson’s book On Freedom from a book shop in Telliskivi during that trip, and I believe that what is difficult has to be examined head on, it’s not worth avoiding it – it’s the pursuit of art (also science) that we don’t avoid trouble, but don’t go looking for it either.

I read an article by Gregori Yudin on my phone while strolling around Balti Jaam market, trying to understand what was happening. War is a total negation of freedom. The violence done within will always find a way to manifest outside as well, that is what I thought then. Here is what I think now: changing scenery is freedom. Drawing borders is hard, as we share so much. But as far as how my thinking has changed – now the need for borders seems even more pronounced. The entities these borders should be erected between are in constant movement though, as things are more akin to constellations with dependencies than clearly divided sectors. Sanctions is an example of one kind of performance of drawing lines, an attempt to define how to affect but not to be too affected. We need to understand the importance of being able to draw these lines, even if only temporarily. The Tallinn trip crystallised this thought for me: accepting the unfamiliar in the world is sometimes made easier by displacement in it.

The (art)world wants to show compassion and solidarity with the ones suffering, but as the issue is too complex, usually the measures taken fail in comparison. But I do think that the desire (to show support) is genuine, which is important in our somewhat cynical culture(s), and for many in Ukraine it has become tangible and acknowledged in ways it obviously wasn’t before – and all the emphasis and the focus is necessary.

Olga Balashova: Ukraine appeared on the cultural map thanks to the people who gave their lives for it

Olga Balashova is an art historian and art critic, lecturer and researcher of 20th century art. Currently, she is Head of the Board of the Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) NGO аnd adjunct professor in Kyiv-Mohyla Business School. In 2017–2020, she worked as Deputy Director for Development at the National Art Museum of Ukraine.

After the full-scale Russian invasion just about everything changed for me and my colleagues. At first, the world narrowed to the space between the walls of my apartment and the closest people nearby. When war is so close to you that you can only plan your life until the next morning, you feel very disappointed that the art world didn’t change at all. Art people and institutions continue to live their own lives at the same pace. Your world collapsed, but all practices outside Ukraine remained the same – same biennials, same art fairs, same events with the same topics. Business as usual. So, we began knocking on every door to be heard and to be present. And we were heard. We did a lot of unplanned exhibition projects in Venice, Washington, Boston, Berlin and Sarajevo. We gain support from the international art community in the form of emergency aid.

In 2022, our small organisation – the Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) and the Ukrainian Art Emergency Fund foundation (that we created with our friends and close colleagues after 24 February), unexpectedly had the opportunity to cooperate with international organizations such as UNESCO, or receive assistance from large renowned foundations such as The Sigrid Rausing Trust, The Andy Warhol and Tiger Foundations. Thanks to these institutions and the beautiful people who work there, we were able to support dozens of art projects and hundreds of creative people in Ukraine during wartime. But very few things scare me as much as long-term plans. Ukraine appeared on the cultural map thanks to the people who gave their lives for it. But will we be able to integrate into a detached and cynical art world, which will continue to live its life even after Ukraine’s victory, and what will happen if we don’t win the war?