Tai Shani’s work displays intricate layers exploring feminism and matriarchal utopias, and examines socio-political landscapes in a remarkably nuanced manner. Her candid engagement with political and humanitarian crises resonates deeply with audiences, initiating discussions, conflicts even. The following conversation, aims to delve not only into her artistic practice but also questions of solidarity, activism, and the notion of otherness that runs like a thread through Tai Shani’s work.

Lilian Hiob: In 2019, alongside Lawrence Abu Hamdan, Helen Cammock and Oscar Murillo, you collectively received the Turner Prize—a departure from the tradition of honouring a single artist. Can you walk us through the discussions that led to this collective decision? What prompted this shift from individual recognition to a shared acknowledgement among nominees?

Tai Shani: We all met for the first time and in that meeting we all felt similarly, that it felt like the right thing to do. Even though our practices and approaches are really different, all of our work is concerned with ideas around power, how societies are organised, and justice, so it felt counter-ethical that only one of us would win.

We made that decision quite quickly and it felt very much in the spirit of the moment. It was at the end of a period that felt very hopeful, especially for people in the UK. There was a real mass movement behind Jeremy Corbyn and the potential of a socialist government. There was a feeling we were moving towards a more hopeful future and that the years of social justice awareness and education was bringing people to a point of action and results, it felt like a change was about to happen. And it was just before Covid, that again felt like a possibility for a moment of change.

LH: You work across a wide variety of media: from experimental text to film to sculpture, installation, performance, work on paper – can you shed light on your process and how you decide on the appropriate media for conveying specific ideas.

TS: I think it's quite collage-y in terms of process, even though the work itself maybe does feel like it has a very specific thread that runs through it. It often is a mixture of things like problem solving, and then weird translations of affects that you've collected through procrastination. You build a language over years. You build a vernacular or a grammar that you use quite automatically. I often start by writing at the beginning of a project, but the thinking around the writing often leads to other things. Also, every space is different, every context is different and that also informs the way you make work. For example, in Cosmic House (upcoming solo exhibition at the Jencks Foundation in April 2024), it's such a specific context that obviously the beginning of the work is the house itself. It's not thinking what is the exhibition I want to do, but how am I going to respond to this and build an exhibition in dialogue with the space?

LH: How do mythology and fantasy serve as tools for you to address contemporary issues or engage with societal norms in your work?

TS: Fantasy is a blueprint for how our desire functions; I don't think any of us are really outside of it. There's something about the archetype-ness that I find interesting – you find certain archetypes in different cultures, primal storytelling about relationships, how we behave, justice, love, about how we are in the world that crosses cultures. I find it interesting how Antigone, which is one of my favourite plays, one of the most adapted plays in the world, is a deeply political play. And it's one that has been relevant for thousands of years.

The first time I read Sean Bonney's poetry, I was very affected by it because he wrote in extremely euphoric and impassioned way about the possibilities of political emancipation. He talks to it in a poetic, delirious way that was very affective for me. Or how Jackie Wang writes about the communist affect. I think there's something about the effect of a horizon that is in my work, a sense of the possibility of things going towards something. It’s a bittersweet feeling always and it's also violent in itself because our lives are short and history is long and the horizon is very far away. Sometimes it can be very difficult because history not symmetrical, it's not balanced. You might endure only disappointments in your lifetime while contributing to the dismantling of hierarchies; you might never experience the joy of seeing a change, but you have the joy of solidarity, of sharing in a vision that people before you have participated in, and you enjoy.

You are also already benefiting from the fruition of efforts of people that went before you, that fought in really dangerous conditions so that you can enjoy certain things in safety – to be a feminist, to be anti-racist. There are things that have come before you. There has always been a drive for egalitarianism, there is a desire to be free from the violence and the oppression of poverty, of racism, of gender, of sexual expression. I don't see what else is worthy of that form of engagement if you're not religious than trying to imagine something better for us. We deserve better, really.

LH: How has your engagement with feminist discourse and visionary futurism evolved from the piece DC Semiramis (2018) which brought you the Turner Prize in 2019, to the upcoming solo exhibition The Cosmic House at the Jencks Foundation in April 2024, which you have described as a dream come true invite (congratulations on that!)?

TS: I became interested in feminism through art making. There wasn't a moment that thought that everything is upside down or constructed in an unfair way. At the beginning I was interested in a very girl bossy idea of what feminism was. While I was teaching at the university, I became aware and orientated towards a queer, intersectional feminism, but I think it all started for me as I tried to understand the sexual and gendered violence that I experienced as a young person growing up in a patriarchal world and seeing the social awakening around ideas of social justice. Conversations around sexual consent really blew my mind when they first started happening because as a young person, I was completely illiterate around these things.

This made me educate myself more on these teachings and it became more complex. I rejected essentialist feminism and understood that in a patriarchal system – and everyone exists in that system, even though we don’t benefit equally from it – it's not about the essence of being a woman or a man that predisposes you to be patriarchal. It's a system that empowers and facilitates the desires of a group of people that happen to be historically men. But women’s specific subject position, like race and class, puts them in receipt of benefits from this system as well, and they also contribute to it.

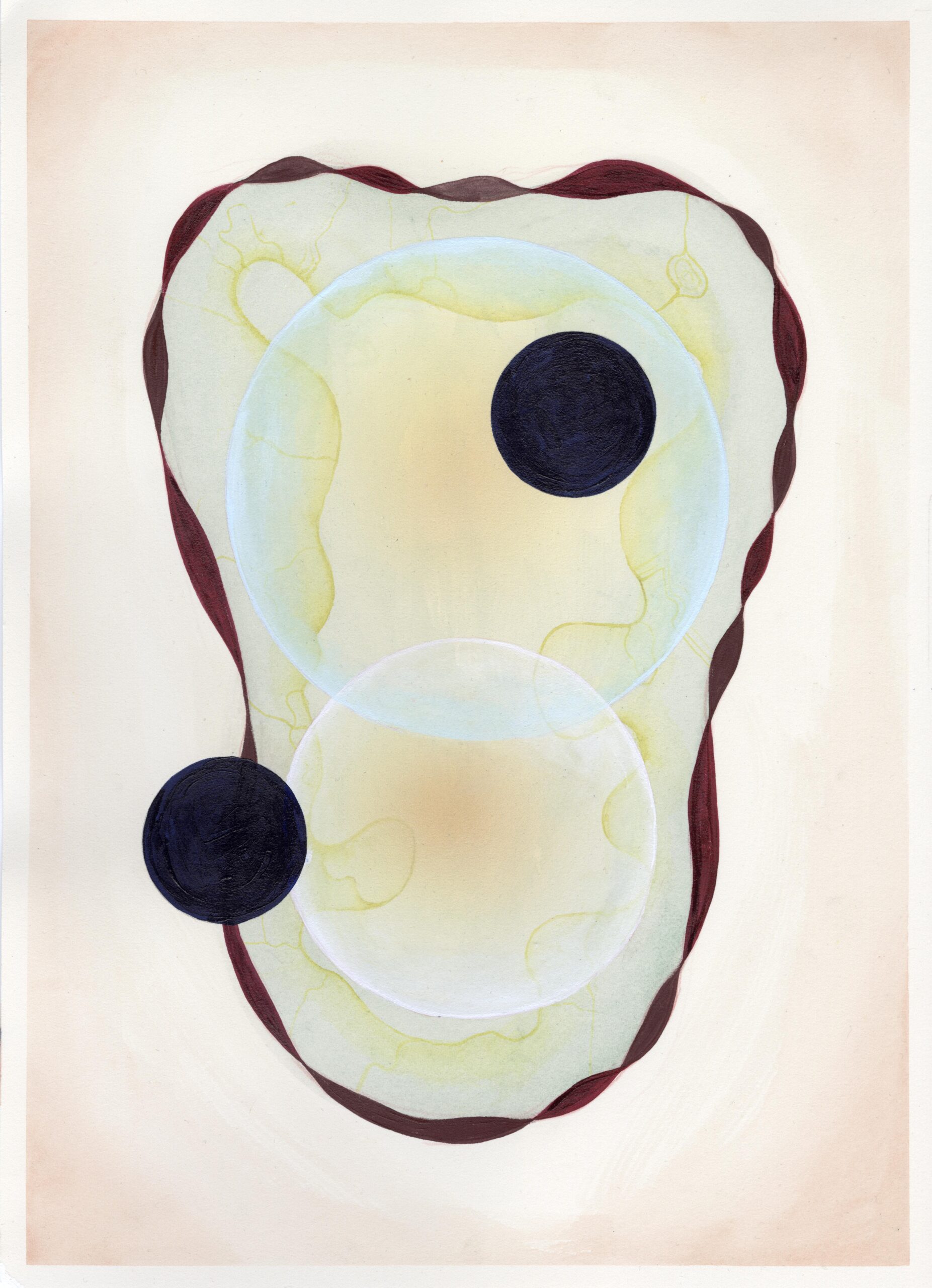

Bodily Remains and All the Bodily Remains that

Ever Were and Ever Will Be, 2023. Courtesy of the artist

LH: Tai, your political convictions have been clear long before the latest escalation of conflict in the Middle East in 2023. How does your steadfast stance as an artist intersect with these evolving dynamics, shaping your creative practice amidst charged socio-political climates?

TS: My work is concerned with ideas that are adjacent to it, but it’s not completely intertwined.

I lived in Israel for eight years; my family are Jewish on both sides. My grandmother on my dad's side moved there in the 1930s. She was fleeing the rise of antisemitism in Belarus. My mom was born a month after the camps were liberated, after a failed abortion. Every single person from my family who didn't die in the Holocaust is buried in Israel.

When I lived in Israel, I had a very loose sense of right and wrong around the politics towards Palestinians in Israel. And I knew I couldn't serve in the military – I'm a pacifist and this is wrong – that was something that was definite for me, but I didn’t have an explicit articulate position around it, like young Israelis that are refusing to serve now that speak towards a colonialist discourse.

I started to feel called to speak towards on it in 2017, when Jeremy Corbyn, who was leader of the Labour Party at that point, started to be accused of anti-Semitism because of his position on Palestine and Israel. I then felt compelled for the first time in my life to say, I'm Jewish, and I don't think that's right, I felt that I had a position to speak from. My mother is considered a Holocaust survivor by the Germans, I do feel a moral duty to call out genocide. I don't think that criticising Israel is anti-Semitic. I think it's our duty towards each other as well to be critical of atrocity and it's our duty towards each other as humans to be protective of each other's lives. We live in a fascist age and I think many people are unable, unwilling, incapable of seeing Palestinians as humans.

LH: It's perplexing how our perceptions of nations, humans, races, beliefs and species are often clouded by a sense of "otherness." I feel we as humans have reached the point where we are so alienated from everything, disconnected from one another and the intricacies of our shared struggles. This is why I value this conversation so much with you Tai, for highlighting the worth of every voice and reminding us to nurture empathy towards each other – the cornerstone of our collective humanity.