During the 1990s, Eastern European contemporary art discourse experienced heightened international interest, as the collapse of the Soviet system paved the way for a free exchange of ideas between East and West. At the heart of this transformation were newly established local contemporary art centres, which became vital catalysts for artistic dialogue and exchange throughout the following decade.

The Soros Center for Contemporary Art in Estonia (SCCA; Estonian Centre for Contemporary Art or CCA since 1999) was one of the 20 art institutions established after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, across 18 Eastern, Central European and Balkan countries.

During his university studies, Soros became acquainted with the ideas of the philosopher Karl Popper regarding open and closed societies and Popper became his mentor. Soros contrasted two societal models: a closed society, characterised by the lack of freedom of thought and action, as well as authoritarian submission to imposed rules, whereas an open society values dissent, individual equality and freedom. Soros saw Western liberal democracy as an example of an open society, while, in his view, the Soviet Union was a perfect example of a closed society. As a result, he directed a large number of financial resources to the Open Society Foundations, through which he aimed to support the development of countries that were no longer closed societies.

Networks of conspiracies

Throughout his philanthropic career, Soros’ goals have come under intense criticism and accusations in the countries where he has operated. Right-wing media in the US has been speaking against Soros since the presidency of George W. Bush, when he actively opposed the 2003 invasion of Iraq. In the eyes of right-wing populists, Soros is personally responsible for the decline of Western civilisation and attacks against him continue in full swing. Even more, they seem to pick up speed as right-wing populism is gaining ground globally. The severity of the situation was highlighted by the 2017 state-wide campaign against Soros initiated by Viktor Orbán’s government, during which eight million Hungarian citizens were sent leaflets outlining Soros’ alleged plans to bring millions of refugees to Europe and undermine local culture through the ideology of multiculturalism. In 2017, a total of 19 million euros were spent on vilifying poster campaigns. Ironically, Orbán had once studied at Oxford University with the support of a Soros scholarship; however, he has since compared the fight against Soros to historical battles against the Ottoman Empire, the Habsburg dynasty and the Soviet Union.

Critical perspectives from the art field

In the field of culture, the activities Soros initiated have been analysed through the lens of colonial theory, critically examining the homogenisation of cultural fields in different Eastern European countries and the rise of a unified East European discourse after the network of art centres was established in the former Eastern bloc countries. Here, I would like to mention that at the time of writing this text, I have been working at the Estonian centre to a greater or lesser extent for 11 years. However, the period I am looking at here, predates my association with the centre, so I could claim a kind of objective perspective. This text could be seen as an attempt to look back at the development of the centre and the issues that arose in connection to it. Since I have not analysed the archival documents of other centres, I will refrain from making broader generalising claims. Especially because the critique of Soros’ activities is based on the principles in which the network as a whole operated, I will try to test these ideas based on the archive of the Tallinn centre.

Based on its statute of 1992, the SCCA’s activities were listed as follows:

Since the centre’s funding significantly exceeded the national cultural funding in Estonia, it is important to understand the trends and the type of art scene it helped to develop. The centre distributed grants until 1998. By that time, the central funding body for culture had been established by the state in the form of the Cultural Endowment of Estonia, which continues to operate to this day. The grant distribution process relied on the expertise of the local centre and decisions were made by the centre’s board, which included art historians actively participating in the art field. The members of the board changed, which resulted in shifts in the priorities almost yearly – each board had its own direction and it responded to developments in the art field in its own way.

The network has been criticised for shaping a unified discourse of Eastern Europe in the countries where the centres operated. According to Serbian art theorist, Miško Šuvaković, with the creation of the network, similar artist positions began to emerge in different countries at the same time and both the content of the artworks and the media the artists used became increasingly similar. Šuvaković coined the term “Soros realism” to describe the phenomenon of the 1990s,

According to art historians Boris Buden and Anders Härm, a crucial component of Western self-consciousness was dissolved, the wild Other. After the Soviet Union collapsed, Western support models were used to re-establish this East-West difference, which led to a distorted image of a unified Eastern Europe, and one of the characteristics that was the construction of the Eastern European self-image, according to the expectations of Western curators and institutions.

The first director of the SCCA, Sirje Helme has said that local institutions were left with relative freedom to shape and develop their activities based on the needs of their local art field.

The so-called Soros Bible and its field of influence

The funding model and centralised principles of the art centres (outlined in the manual intended for Soros centres, which some likely seriously and others ironically refer to as the Soros Bible

According to Helme, the activities of the centre were influenced by the particularities of the local fields. For example, the centres in Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania had similar profiles, while in Poland and Hungary, contemporary art centres already existed before the Soros system was established.

Both providing scholarships and organising annual exhibitions were a key part in the work of the centres. Based on archival documents, it is difficult to find a clear hierarchical division; for example, in 1993, funding was provided for publications, art programs on national television, graphic art, periodicals, the Saaremaa Biennale, participation in international group exhibitions, art initiatives in small towns, artists from the older generation, new media art, young and experimental art, sculpture, and more. In the 1996 funding applications, a wide spectrum of gender, media, and art movements was represented. Support was given to art historians, fashion, painters, participation in conferences, collectives and individuals, sculpture, printmaking, and participation in international exhibitions. The general themes of the annual exhibitions were formulated through discussions between SCCA staff and local experts. Participating artists were chosen by a committee, which included both local and international experts and the recipients of awards were determined by an international jury.

When working through archival documents, it becomes clear that Soros’ unified materials for the centres were meant more as supportive guidelines. It would be too simplistic to interpret them as instruments of hegemonic power without analysing each individual case.

According to Croatian cultural critic Boris Buden, the OSF project and the idea of a unified post-Soviet society ultimately collapsed in 2018, when the first Soros centre, which had opened in Budapest in 1985, and the Central European University (established by Soros) were forced to relocate to Berlin and Vienna due to pressure from Viktor Orbán’s right-wing radical government.

According to Elnozahy, this funding model is blind to cultural specifics, forcing artists to fit into categories such as “socially inclusive artist” or, since the 2011 Arab Spring, “revolutionary artist.”

New media – what was driving it?

Substance – Unsubstance

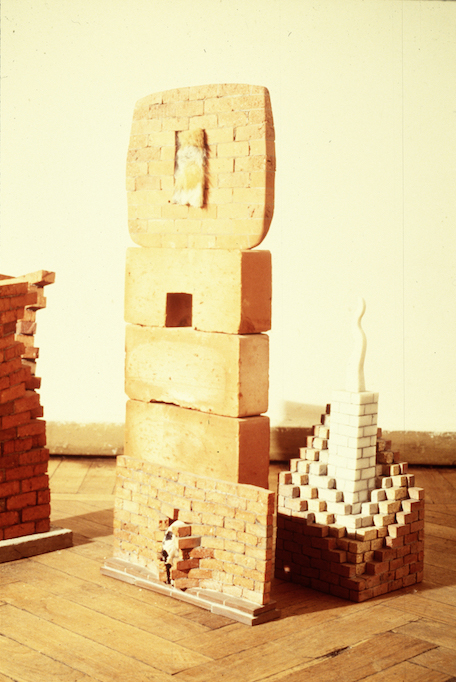

Another significant characteristic of Soros realism is the emergence of new media art. New media art can be understood as art related to new technologies (in the 1990s, for example, that included video, photography, installation and digital art) and the dematerialisation of art itself.

However, this rise can be more closely linked to larger societal changes, such as the end of the Soviet occupation, which brought the tradition of Western contemporary art to the Eastern bloc, the opening of borders and the spread of technological tools globally. The manual sent to the Soros centres did recommend supporting media that were not yet widely used in the local art scene but it did not dictate in what form new art should emerge. For example, in Lithuania, the centre supported new media art to a relatively small extent, focusing instead more on the modernism of the 1960s and 1970s. This shows that the rise of new media was not uniform or inevitable across all the centres of the Soros network but rather depended on the local art field and its internal dynamics.

This does not mean that I underestimate the impact of the Soros centres on the cultural fields of post-Soviet societies, but I would also like to suggest a moderate determinism of technological development itself. I would dare to say that the role of new media in the Estonian art scene was an inevitable part of societal development, and the impact of technology on art should neither be under- nor overestimated. The shift of physical media to the background during this period could also be tied to the opening of borders and global political changes. Global networking allowed cultural phenomena to exist simultaneously in multiple intellectual spaces, shifting locality into a multicultural public sphere. Therefore, the rise of new media art may be more of an inevitable result of societal changes, alongside which Soros realism unfolded during the 1990s.

CULTURAL PERFORMANCE

Šuvaković has written that Soros realism produced the dominant influence of Western multiculturalism and liberal democracy in post-Soviet societies, shaping the taste preferences and public opinion (doxa) of their middle-class intellectuals through art. At times, the critique of Soros realism places an overly significant role on the activities of the centres in the wider societal context. In Pierre Bourdieu’s framework, doxa refers to the unconscious competence of an individual, shaped by societal institutions, that influences their taste preferences. The influence of the Soros centres on the development of the local art scene should not be underestimated but I would be cautious about how much weight we should assign to it. No doubt, the centres did hold a central position in the art scenes of the 1990s but based on the materials I have reviewed, I cannot make such a bold statement.

While Bourdieu’s sociology looks at the development of individuals primarily from top to bottom, in analysing Soros’s influence, we might consider using Jeffrey Alexander’s concept of cultural performance instead. Alexander emphasises the symbolic creation of meaning and its impact on constructing social reality. In this framework, the art worlds created with Soros’ support could be treated as performances, presented both domestically (through grants, annual exhibitions, archiving) and internationally (such as the 1999 Moderna Museet exhibition After the Well, Manifesta, or SCARP

A malicious or careless handling of archival sources allows the endless construction of all sorts of narratives. For example, in the Estonian centre’s archive, we can find jokes and caricatures exchanged between past and present staff – Soros is sometimes referred to as “God” and texts about him are called the “Bible”. In the correspondence between the centres, there are lines like “Everything you wanted to know about information but were afraid to ask...”.

These notes reflect the employees’ proclivity for irony and humour. They expose the ‘flesh’ beneath the often-concealed body of the past, making the archival material feel both delicate and alive. We live in a time when private space has almost disappeared and a large part of our lives is in some way public. Writing this text reminds me of how fragile the reality I inhabit daily is, and also that openness can be interpreted by some as being closed and performance as reality. The discourse surrounding East European art has long been accompanied by a shadow of generalisations. And because of that, we must be cautious when taking critical constructs to analyse other diverse cultures, as this creates the risk of reinforcing stereotypical generalisations about the cultural and social unity of the former Soviet countries.