Terje Ojaver (b 1955), one of the most idiosyncratic and prolific Estonian sculptors, has produced a remarkably diverse body of work ranging from small-scale figures to public monuments, from semi-abstract forms to expressive or surrealist-inspired figurations, from bronze sculptures to those made of non-traditional, lower-value materials, from more classical genres and formats to conceptual installations, performance and land art. In 2025, Ojaver is celebrating a creative career spanning four decades with a solo show called Serpent at the Tartu Art Museum. Ojaver has been exhibiting in Estonia and internationally since the mid-1980s, when she completed her studies at the Estonian Academy of Arts (formerly the State Art Institute).

Ojaver’s heterogenous approaches, reflecting the artist's endless curiosity and responses to her constantly evolving world and her personal life experiences through three-dimensional forms in space, presents the viewer and reviewer with an intriguing task: to find out the common threads and recurring topics that help us make sense of the artist's modus operandi, to understand how she sees and responds to the world through her art.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, as a young sculptor at the beginning of her career, Ojaver attracted attention with her participation in highly esteemed group exhibitions dedicated to small sculpture.

Hybrid women with the artist’s face

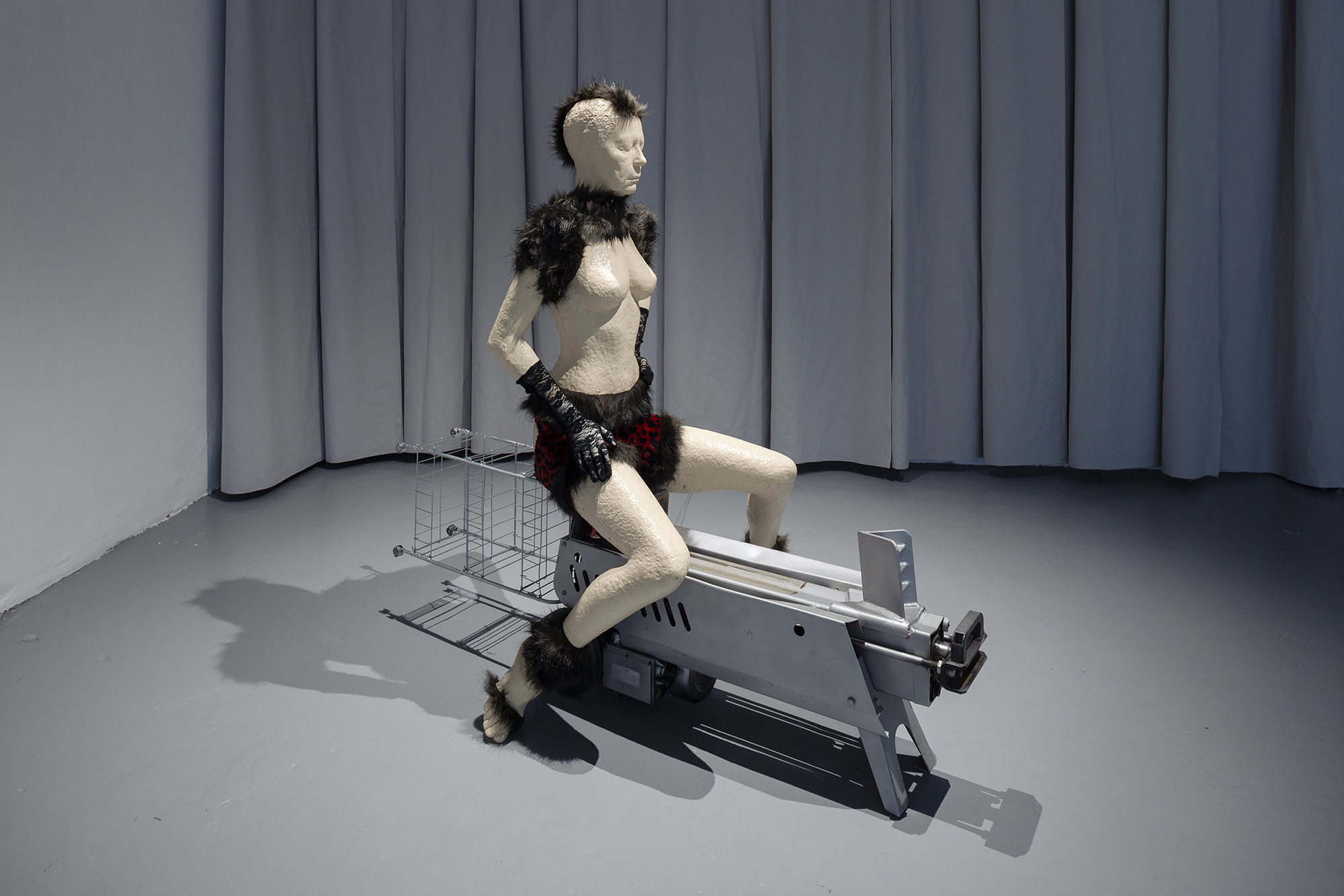

Ojaver's most programmatic work, which occupies a central place in her work of the past 15 years, are free-standing silicone figures of women or hybrid – half-female, half-animal – creatures for which the artist uses casts of her own body and face. Often entitled self-portraits, these sculptures refer to different roles and identities in a woman's life – wife, mother, worker, creator etc – doing so indirectly through symbolic figures which embody deeply personal experiences and corresponding emotional states. In a gallery space, these works are often grouped into theatrical mis-en-scenes or fairy-tale-like narratives that speak directly to our emotions or subconscious.

Visually, however, these female figures or hybrid creatures do not have much to do with the everyday reality of women living in the modern, urbanised and post-industrial world. Instead, the artist seems to evoke certain emotional layers or patterns of identification in our psyche through the use of archaic archetypes and a mythological imaginary. Among these hybrid fantasy creatures, we find a turtle whose shell is a mound of frying pans, a tired-looking woman with soil-covered hands and "heavy feet" (an idiom for pregnancy in Estonian), a camel pressed to the ground, a fish covered with armour made from lace, and other creatures, all of whom are endowed with the artist's own facial features. In many cases, the symbolism is easily recognisable: the camel is a beast of burden; the turtle woman is weighed down by a mountain of cooking pans; the female figures are either Madonna, Venus or more archaic archetypes, such as a toiling peasant woman or clairvoyant. The artist mixes more universally recognisable mythological references with local ones, for which she turns to Estonian heritage and folklore. She finds inspiration in pre-modern, archaic rural culture where there were no fixed boundaries between the natural and the human world or the animal world and the human world.

Visualising women's associations with the land, nature and the animal realm may be seen as the foundation for her personal understanding of feminism: in a recent interview, Ojaver has described herself as a soft/organic

A towering giant and hope for the future

One of the works in her solo show Serpent in Tartu, Giant Woman with a Pitchfork is the artist's response to the Russian war of aggression against Ukraine and how it has affected the borderlands with Russia – the Baltic states and other countries living in existential fear. Kaarin Kivirähk has described the work's anti-war message as follows: an old giant woman "is not a destroyer of the Earth, but a cultivator, a cleaner of the land covered in mines, a collector of garbage, a sower of new crops. (...) She is going about her business: whether there is war or not, the fields need to be cultivated, and food needs to be put on the table: life must go on."

But there is no doubt that the Giant Woman with a Pitchfork also functions as a figure of hope, given its symbolic power to embody the ideas of (women's) life-force and the continuity of generations. A couple of years ago Terje Ojaver participated in the project Invisible sculpture,

Ojaver's works are, therefore, rooted in both the deeply personal and the collectively experienced world around us. The choice of artistic approaches, techniques and materials might vary, but the choice of relying on mythical and symbol-laden storytelling always takes precedence. She does not deny the facts of life or realities of an unfair world, but neither does the symbolic and often humorous translation of those into works of art crush the spectator.