The New East is a term used to mediate the contemporary culture of the ex-Soviet and Eastern bloc countries for Western audiences. Since its rise in the early 2010s, the label has received both adoration and criticism. It refers to and identifies a visual narrative which is sought after by visitors from outside the region but often also presented by local artists, musicians, designers and other creative minds.

We asked six artists, curators and writers from Estonia and the Baltics how they view the term New East today, more than 30 years after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Do people relate to this label, which evokes an outsider’s gaze but also has been embraced by some in the region? Are there any particular traits that unite the visual culture of the former Soviet countries?

Andres Kurg: We need to deprovincialize the New East

Andres Kurg is a senior researcher at the Estonian Academy of Arts in Tallinn, Estonia. His research looks at architecture in the Soviet Union from the 1960s to 1980s.

The term New East first brings to mind previous similar terms, like New Europe or Emerging Europe, that appeared in the early 2000s around the enlargement of the European Union and aimed to represent the culture and politics of the new member states. At the time there was a heightened interest in the built heritage of the late Socialist period that found its way into many coffee-table books and popular exhibitions, where it was shown as bizarre and otherworldly, like “spaceships” left behind by “aliens”, deeming these structures to be exceptions to the modernist norm originating from the West. Although the New East is applied to a broader territory (including Russia, Central Asia and the Caucasus), there are similarities in the ways in which these countries and their cultural output is represented under the label. There still seems to be a strong emphasis on the ruins of the so-called Second World, on socialist modernism that is thus exoticized as a quirky divergence from the core modernism originating from France or Germany. And as an exotic other, the New East is at the same time a projection of the promises of indulgence and pleasure denied back home.

The question then would be how to gain control over the representations of the New East or, perhaps more realistically, add new analytical renditions to the existing clichéd ones? I guess more than bringing out new and “exotic” material on Eastern Europe, we need to theorise it from our own point of view and show the interconnections and entanglements of modernities that have been kept separate; to deprovincialize the New East. That does not mean writing Eastern Europe “into” an existing global narrative, but realising that in coming into contact with the socialist heritage and the contemporary culture of the New East, the Western narrative and its corresponding hierarchies are themselves bound to change.

Katja Novitskova: The New East as a temporary trend has or is about to lose relevance (and that's ok)

Katja Novitskova is an artist born in Tallinn and currently based in Amsterdam, the Netherlands. Her works explore the touching points between visual culture and science fiction. She represented Estonia at the 57th Venice biennale in 2017.

Perhaps I have been a bit out of touch (or more like lumped into another category), but I have never really consciously thought about the New East as an umbrella term before. And definitely not in reference to myself or my artistic work. I can sort of understand where it might be coming from – based on examples, such as Demna Gvasalia, Cxema and Tommy Cash, we can see that it's about a generation of people who grew up through the dark, poor and free (in our memory) 1990s and whose aesthetic and cultural sensibilities were radically shaped by the consequences of the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Due to the arrival of market economies in the region, this generation has been able to learn to speak a new global language, which it then used to shoot out from the local cultural spheres onto the stage of international exchange. From the outside perspective there is perhaps an uncanny peculiarity and commonality to this cultural output that has become a distinct trend that also fuels itself. But what is interesting to me are the parallels that one can spot between the rise of let's say Gvasalia and someone like Virgil Abloh, the first being a child immigrant from Georgia to Germany and the second, a child of immigrants from Ghana to the USA – these are parallels that go beyond regional specifics. I try to see what I do more in this vein, how it extends outwards from my background and allows me to work on contemporary issues in dialogue with the wider world. I think the part of the New East that is about generational truth and experience has already grown roots into contemporary culture, but the part that is a temporary trend has or is about to lose relevance (and that's ok).

Hansel Tai: Estonian Gen Zs are not afraid to confront and mutate the Soviet aesthetic

Hansel Tai is a Chinese-born artist and jeweller based in Tallinn, Estonia. His work focuses on queer culture in the post-internet era.

I think one of the most interesting aspects of the term New East is that it was a cliché coined by the West – outsiders gazing in. Personally, I cannot imagine anyone wanting to embrace this term. It seems inherently limiting and evokes inferiority, doesn’t it? As though describing something new, but already delineating its brilliance as merely regional.

One cannot help but think how the New East compares to the Old West or the New West? In many ways the “New” in “New East” was never clearly defined. But there was indeed a cultural big bang after the collapse of the USSR and Eastern Europe’s newfound freedom attracted Western media rushing into the liberated lands in order to observe them under a closer lens.

Today, Generation Z across the world uses the same iPhone models, and on their iPhones the same Netflix shows are being streamed. In many ways, we are merging into a global hotpot (quite literally, because of climate change). In order to claim your distinct identity in this sea of sameness, you need to look towards your heritage, go deeper, back in time.

In this sense, the term New East is a reminder of diversity, celebrating differences, it does not erase but reclaims. I think people often forget that a movement and a cultural aesthetic always consists of individuals, and shaping it is the task of every young person today. Maybe a New New East appears (can I coin this)? For me, this new development perfectly reflects the art scenes in Estonia. One of the best examples is the fashion culture. The Estonian Gen Zs are not afraid to confront and mutate the Soviet aesthetic into something else. And there is much to express!

Inga Lace: We are poignantly reminded of the lived experience of being in the East

Inga Lāce is the C-MAP Central and Eastern Europe Fellow at The Museum of Modern Art, New York and a curator at the Latvian Centre for Contemporary Art.

I think we are poignantly reminded of the lived experience of being in the East every time the periodic cycle of geopolitical calamities starts again somewhere in the region. Just in the past couple of years, we’ve witnessed an uprising and the subsequent violent crackdown in Belarus. In addition, in the summer of 2021, borders were particularly under assault: the Lukashenko incited hybrid war – a refugee crisis – at the Latvian, Lithuanian and Polish borders with Belarus. Then, military tension at the Ukrainian and Russian border, and in early 2022, the unexpected uprising in Kazakhstan that destabilised a much larger area neighbouring China.

While the term New East seems well suited to describing largely fashion, design, and pop-music related trends, I would say that terms like these often lack a critical quality and fail to account for the history of the post-socialist and post-Soviet areas. Whichever terms are used, it is important to consider the diverse and dynamic history of the region in order to understand the present. The omission of that complexity leads to the right-wing nationalist tendencies, disguised as patriotism.

I think that trauma heals slowly and that is also an active process. Looking for new wor(l)ds to talk about our experience, conduct research and interpret the region’s history from a contemporary position is still relevant and will be for years to come. So, there are numerous pressing themes, such as environmental (art) histories and colonialism that need to be analysed from a particular regional position that notably differs from that of the West and prioritises a transnational perspective. We are already seeing exhibitions by artists from a generation whose lives and careers were not marked by the shock of transitioning from the Soviet to the post-Soviet era, which allows them to bring in new perspectives, both aesthetically and content-wise.

Eha Komissarov: Gazing towards the West in a blind and idealising manner might have worked to our advantage

Eha Komissarov is a curator at Kumu Art Museum, the largest branch of the Art Museum of Estonia, where she has been working since the 1970s. In the 1990s, Eha Komissarov became the leading contemporary art curator in the newly independent Estonia.

As a practicing curator of a former Soviet republic, I love the formulation New East. However, its use is not unproblematic – when we talk about art history more specifically, the term New East is often used to refer exclusively to Soviet artists and art discourses. I think that the former Soviet republics in the Baltic region should not be included in this, we should be considered from a different perspective. Our attitude during the Soviet period was clearly anti-Soviet and our gaze was turned towards the West. Even though we did this in a blind and idealising manner, by now we see that it might have worked to our advantage. Today, we see that the former Soviet republics that did not have cultural connections with the West (in addition to art I also mean jazz, rock, pop culture, fashion, lifestyle) are struggling to form a unified front against Russia. During but also after the Soviet period, the Baltic states were desperately looking to differentiate themselves from other (former) Soviet regions, which led to a merging with the West from a different starting point.

Despite restrictions, in the Baltics as well as in other socialist countries of Eastern Europe, a serious effort was made to maintain a dialogue with international art movements. This was a political stance that benefitted these countries greatly later on: they adjusted fast because their crooked relationship to the West helped them escape the cultural shock that hit other Soviet republics hard.

When it comes to the former Soviet Union and socialist republics, it is difficult if not impossible to work the art discourse of the transitional period of the 1990s into a smooth theory that can be easily understood by everyone. We need to communicate very clearly how difficult it was to survive then, to develop and gain recognition – and what the role of art was in this. It is extremely important especially today, taking into account Russia’s political moves in recent years, that we take a stand against its chauvinist attitude and expose the kind of colonial ambitions it has always had towards the former Soviet republics and socialist countries.

Helgi Saldo: The need to define us through the term New East is an issue for Westerners

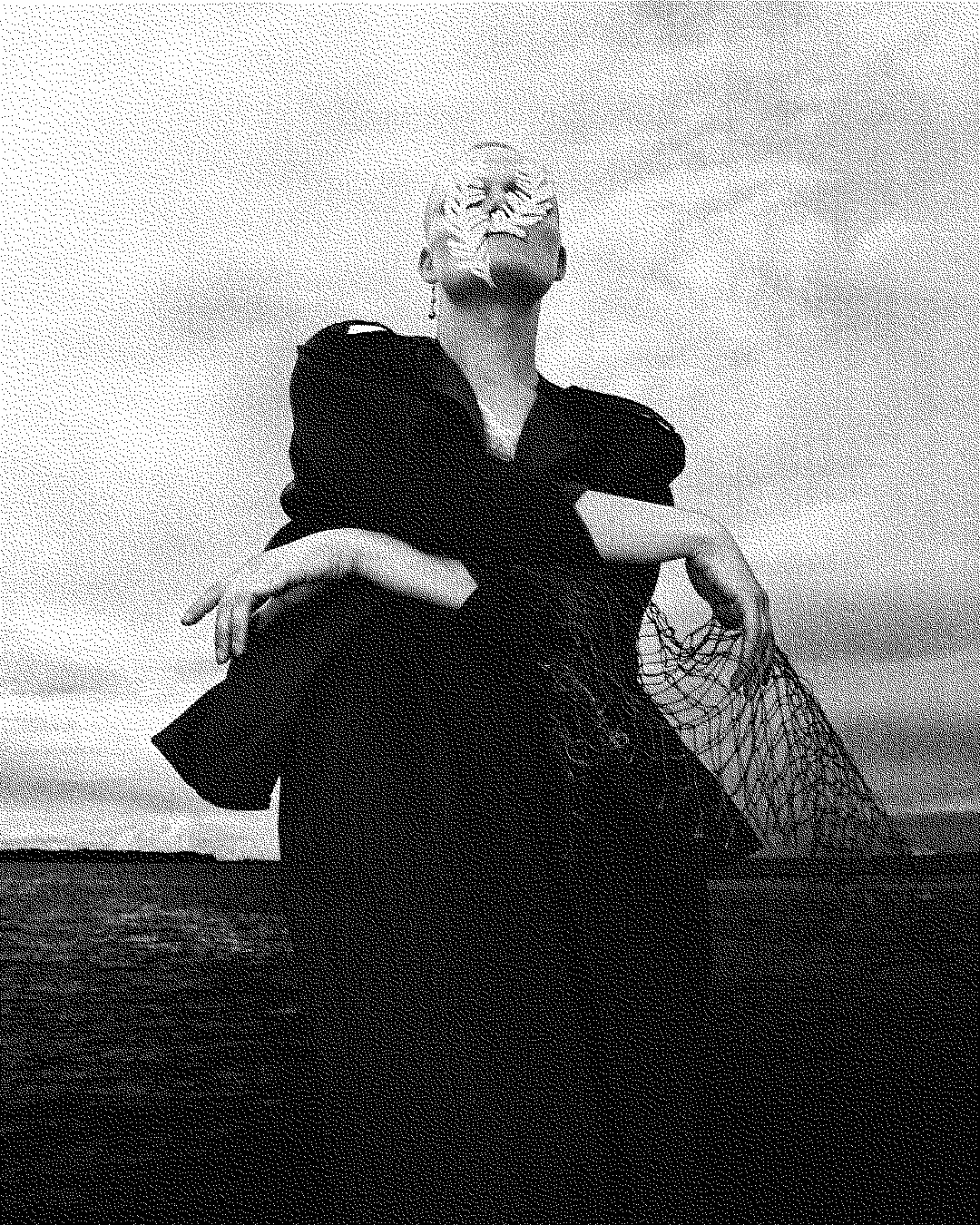

Helgi Saldo is a non-binary drag performer and artist based in Tallinn, Estonia. Find them on Instagram @helgi_saldo and on IDA Radio, where they host the show Homokringel.

I think the need to define Estonians through the term New East is more of an issue for Westerners than anyone else. I define my drag practice as Eastern European body horror, so I can only roll my eyes when I see Estonia promoted as a Northern European country; I find this to be a strange reaction provoked by shame. And the same goes for the part of the West that sees us as somehow exotic and dangerous. Being a small nation is weirdly queer; I see many parallels and similarities in the way in which Estonians and queers must justify their existence or choices to larger groups. I understand the conflict is real and also why these steps are necessary, but I think we should address our history and the present according to who we are, what we need and what we have as a nation, and not worry about how the West defines us, even if our culture is closely linked to the West or we borrow from each other.

The interviews were conducted in January 2022.